Inflation is generally controlled by the Central Bank and/or the government. The main policy used is monetary policy (changing interest rates). However, in theory, there are a variety of tools to control inflation including:

Video

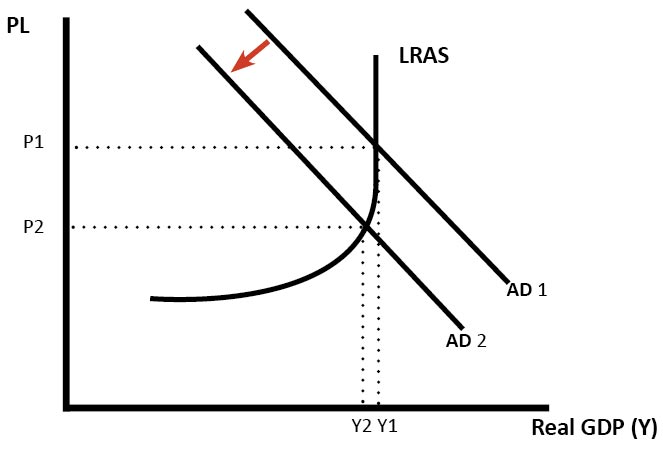

In a period of rapid economic growth, demand in the economy could be growing faster than its capacity to meet it. This leads to inflationary pressures as firms respond to shortages by putting up the price. We can term this demand-pull inflation.

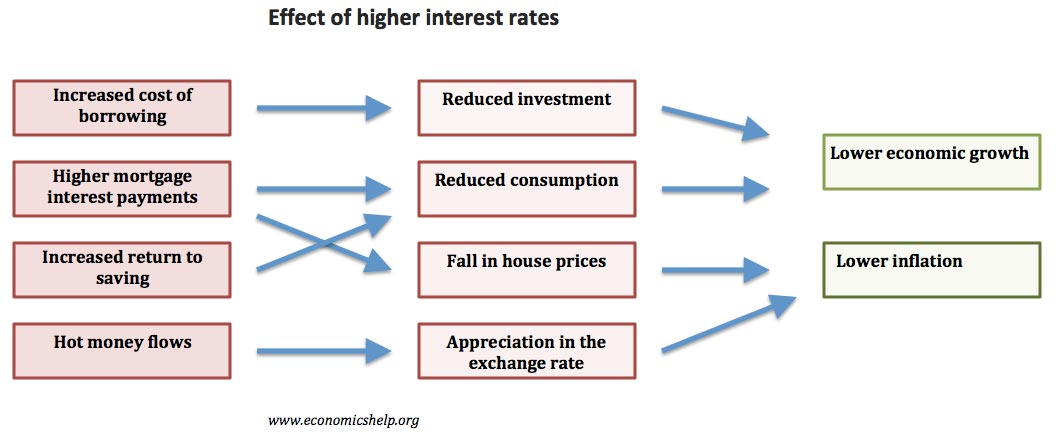

In response to inflation, the Central bank could increase interest rates.

A higher interest rate should also lead to a higher exchange rate (higher interest rate attracts hot money flows) The appreciation in the exchange rate will also reduce inflationary pressure by:

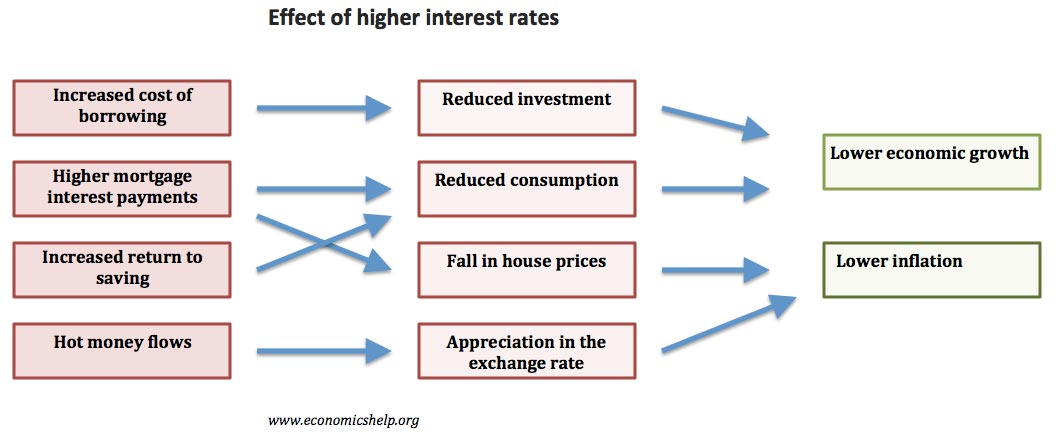

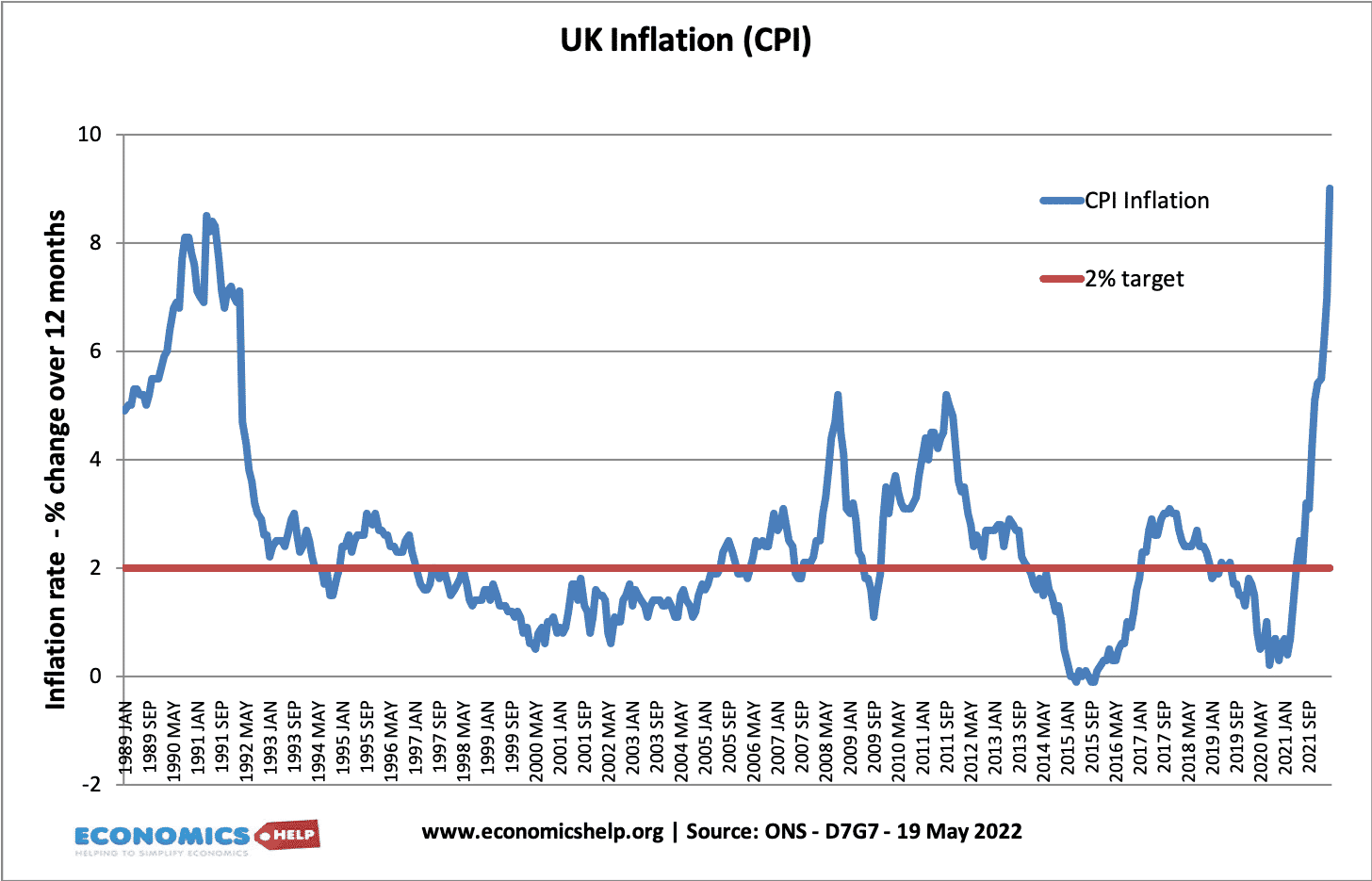

UK Inflation and interest rates

Interest rates were increased in 2022 to deal with the surge in inflation. However, the increase in interest rates is relatively low compared to the size of the inflation. This is because the Bank of England hope the inflation will prove temporary.

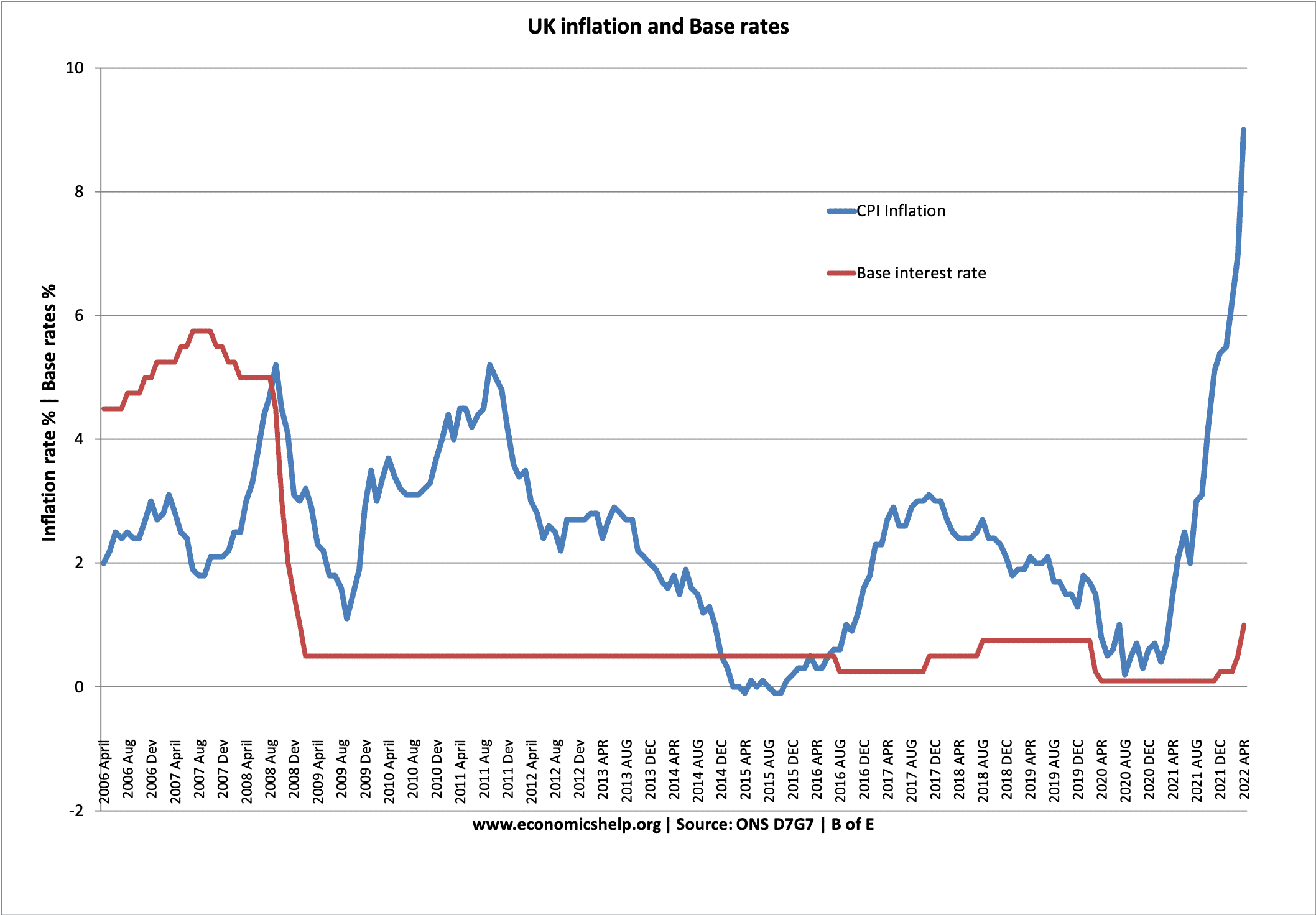

Inflation and interest rates post-war

If we look at inflation and interest rates in the post-war period, we can see interest rates rose to 15% in 1990 to deal with inflation of 10%.

As part of monetary policy, many countries have an inflation target (e.g. UK inflation target of 2%, +/-1). The argument is that if people believe the inflation target is credible, then it will help to lower inflation expectations. If inflation expectations are low, it becomes easier to control inflation.

Countries have also made Central Bank independent in setting monetary policy. The argument is that an independent Central Bank will be free from political pressures and avoid making mistakes like cutting interest rates before an election to curry favour with voters.

To reduce inflation, the government can increase taxes (such as income tax and VAT) and cut spending. This improves the government’s budget situation and helps to reduce demand in the economy.

Both these policies reduce inflation by reducing the growth of aggregate demand. If economic growth is rapid, reducing the growth of AD can reduce inflationary pressures without causing a recession.

Also increasing taxes to reduce inflation is likely to be politically unpopular which is why fiscal policy is rarely used to reduce inflation.

1. Reduce expectations

A key determinant of inflation over time is inflation expectations. If people expect inflation next year, firms will put up prices and workers will demand higher wages. This expectation tends to cause higher inflation. If the Central Bank and government can effectively reduce expectations by making credible threats to bring inflation under control, this will make their job easier.

2. Price controls

With inflation, we will see firms trying to increase prices as much as they can to maintain profitability and deal with rising costs. One way to try to avoid this ‘profit-push’ inflation is to introduce price controls. This is where the government sets limits on price increases.

For example, in 1971 President Nixon imposed a price freeze that he reintroduced in 1973 after winning the election. The price freezes were politically popular for a short time but basically failed. Firms restricted supply and when price freezes ended, suppressed inflation returned with a vengeance. However, it is worth noting that price controls during wartime were successful in reducing inflation. One study by Paul Evans found in WWII price controls were successful in keeping prices 30% lower than otherwise. (though this was with rationing and 7% lower output).

If inflation is caused by wage inflation (e.g. powerful unions bargaining for higher real wages), then limiting wage growth can help to moderate inflation. Lower wage growth will reduce the costs for firms and lead to less excess demand in the economy.

However, as the UK discovered in the 1970s, it can be difficult to control inflation through income policies, especially if the unions are powerful. Also, wage control requires widespread co-operation in the economy, but if firms are facing labour shortages they will be more concerned to get the workers, even if they have to exceed government wage controls.

Monetarism seeks to control inflation by controlling the money supply. Monetarists believe there is a strong link between the money supply and inflation. If you can control the growth of the money supply, then you should be able to bring inflation under control. Monetarists would stress policies such as:

However, in practice, the link between money supply and inflation is less strong.

Often inflation is caused by persistent uncompetitiveness and rising costs. Supply-side policies may enable the economy to become more competitive and help to moderate inflationary pressures. For example, more flexible labour markets may help reduce inflationary pressure.

However, supply-side policies can take a long time, and cannot deal with inflation caused by rising demand.

A country may seek to keep inflation low by joining a fixed exchange rate mechanism. The argument is that if the value of a currency is fixed (or semi-fixed) then this creates a discipline to keep inflation low. If inflation rises, the currency would become uncompetitive and start to fall. In the late 1980s, the UK joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) partly to bring inflation under control. However, targetting inflation through the exchange rate can is difficult and the UK was forced to leave the ERM in 1992.

In a period of hyperinflation, conventional policies may be unsuitable. Expectations of future inflation may be hard to change. When people have lost confidence in a currency, it may be necessary to introduce a new currency or use another like the dollar (e.g. Zimbabwe hyperinflation).

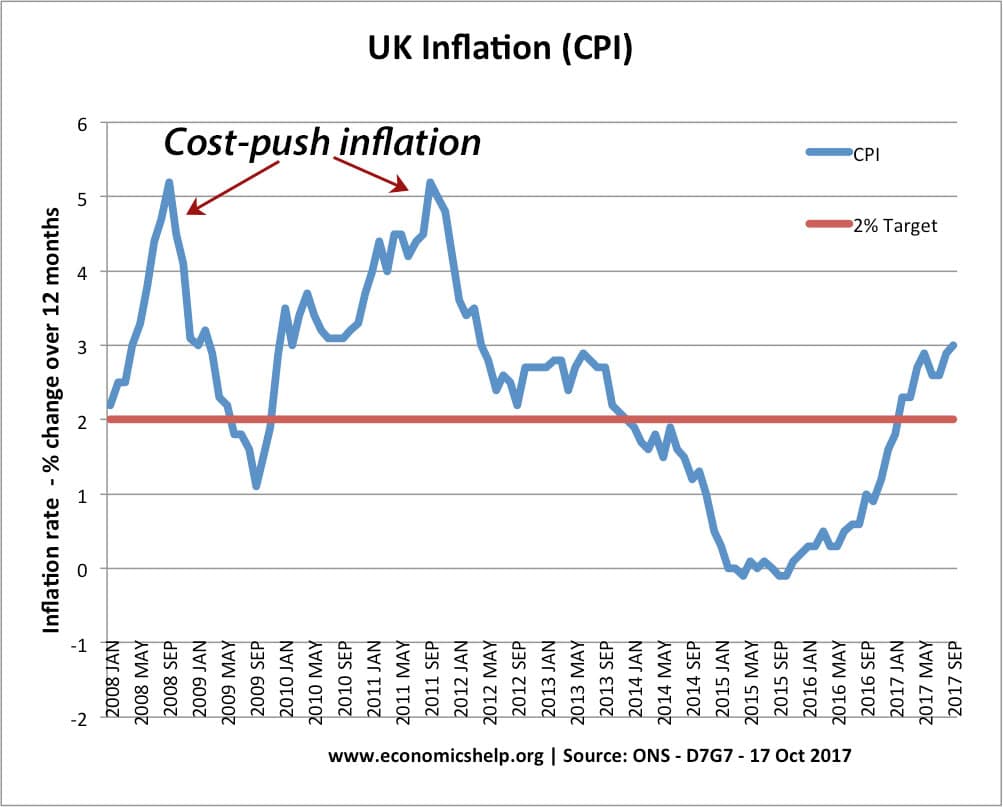

Cost-push inflation (e.g. due to rising oil prices) can lead to inflation and lower growth. This is the worst of both worlds and is more difficult to control without leading to lower growth. In 2022 the world saw a rise in cost-push inflation due to rising energy prices and the end of Covid lockdown causing supply shortages.

Cost-push inflation is more difficult to reduce because it is fundamentally caused by supply problems. Raising interest rates is a blunt tool and likely to cause unacceptably lower growth. This is why Central Banks tend to tolerate a higher rate of cost-push inflation and hope it is short-lived. In the long-term we can try and tackle the supply issues, such as more flexible labour markets, stock-piling oil reserves to deal with crises and policies to increase competitiveness.

Further reading