This Guidance Note provides an introduction to some crucial characteristics of the processes from which public policy emerges. As far as possible it is written in general terms, avoiding references to particular policy environments. The institutional arrangements and working practices of government of course vary greatly from place to place, but we would contend that there are a number of basic features that are often encountered, and that it will be helpful for researchers to be aware of these as they consider how best to engage with these processes so as to achieve impact.

The institutional arrangements and working practices of government of course vary greatly from place to place, but we would contend that there are a number of basic features that are often encountered

Researchers whose specialism lies in the field of government, politics, public policy or public administration will find nothing new in this account, and indeed might want to take issue with some aspects of the approach we have adopted here; there are many different ways of framing the arguments around how policy is made, and much debate around concepts and terms. This piece has been written primarily for the benefit of researchers in other disciplines who may not have had occasion to give much thought previously to how these governmental functions work.

There is no shortage of definitions of what is meant by policy, of varying degrees of usefulness. However, a good starting-point for present purposes is Thomas Dye’s assertion (from as long ago as 1976) that “Public policy is whatever governments choose to do or not to do.” This simple statement introduces three key components:

There is much more to be said about all of this, and there is a copious policy studies literature which addresses a wide range of related issues, including how decisions are made, what are the factors that influence them and who has a voice in them; how decision-makers attempt to balance competing interests; and the disjunctures between original intention, the actions eventually implemented and their consequences. Nevertheless, the fundamental idea of choices by government leading to action is a helpful one to hold on to, and one from which several points follow.

It is . in most systems the executive (government) not the legislature (parliament) which makes or leads the making of policy. This has definite implications for where researchers may choose to direct their policy engagement efforts.

The first is that parliaments may play an important role in raising the visibility of issues through debate, reviewing and assenting to government proposals (with varying degrees of authority to amend them); debating, amending and passing the legislation often needed to enable implementation; assenting to taxation and expenditure; and scrutinising what is done, and making recommendations (which may or may not be accepted and acted on). It is, though, in most systems the executive (government) not the legislature (parliament) which makes or leads the making of policy. This has definite implications for where researchers may choose to direct their policy engagement efforts.

A second point is that decision by government means ultimately decision by ministers (or in some cases by an executive President) – the elected or appointed political leadership . Policy decisions are seldom taken by political office-holders in a vacuum: analysis and proposals are generally prepared in great detail by official advisers (civil servants), sometimes working with ministers’ appointed political advisers (in the UK properly called special advisers), and the advice and eventual decisions are both shaped by the influence and advocacy of a wide range of interest groups in business and civil society, opinion formers in the media, allies and opponents in parliament and the political parties at large, and academic experts. There are thus many potential points of access to influence and inform decisions, but many are quite indirect in effect and their efficacy difficult to assess. Subordinate decisions about the detailed and implementation of policy decisions and the application of policy to specific cases will often be taken by officials without reference to ministers unless the issue is potentially politically contentious or has wider policy implications. But policy as such is what ministers have decided (even if they may not be fully seized of all the consequences of those decisions). As former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said, “Advisers advise, Ministers decide”.

As former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said, “Advisers advise, Ministers decide”.

It is, however, because of the multi-faceted nature of the policy environment that we have tried where we can to avoid in this guidance the use of the term “policy-makers”. It begs the question, who really makes policy? The politicians who decide, the advisers who craft the proposals, the advocates and influencers who create the climate of opinion in which decisions are taken? For this reason we prefer to refer to policy communities, or to policy actors.

If you are reading this, you are probably already a member of a wider policy community, and interested in deepening your membership. However, to avoid confusion we have in this guidance drawn a distinction between policy actors, whose primary interest lies in the formulation and execution of public policy, and researchers, whose principal concern is with the systematic production of new knowledge.

It is tempting to see policy-making less as a process, and more as a politically-charged domain of perceived problems, interests and competing proposed solutions in which decisions somehow emerge from complexity. Yet if the aim of public policy is to translate the political intention to make improvements in the world or to respond to challenges into practical outcomes, the notion of process – a series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end, unfolding dynamically in time – is a useful corrective to more static descriptions of the policy environment which focus on the interests or competences of the actors. There are many ways of describing or depicting policy-making as a process, but over the years different versions of the policy sequential analysis model have been adopted by many scholars; this kind of model provides a simplified understanding of the complexities of the policy process by presenting it as a number of stages, each of which raises its own specific issues. Such an approach has, for example, been used to investigate the differing uses of evidence at different stages of the process.

How evidence contributes

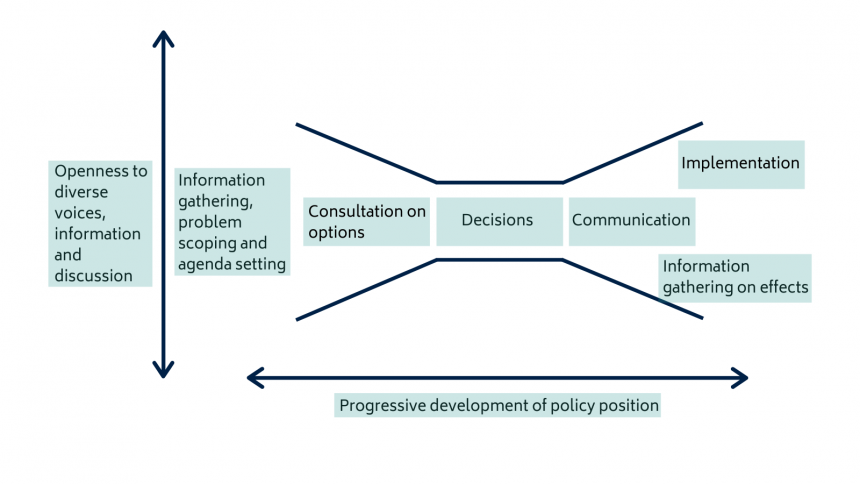

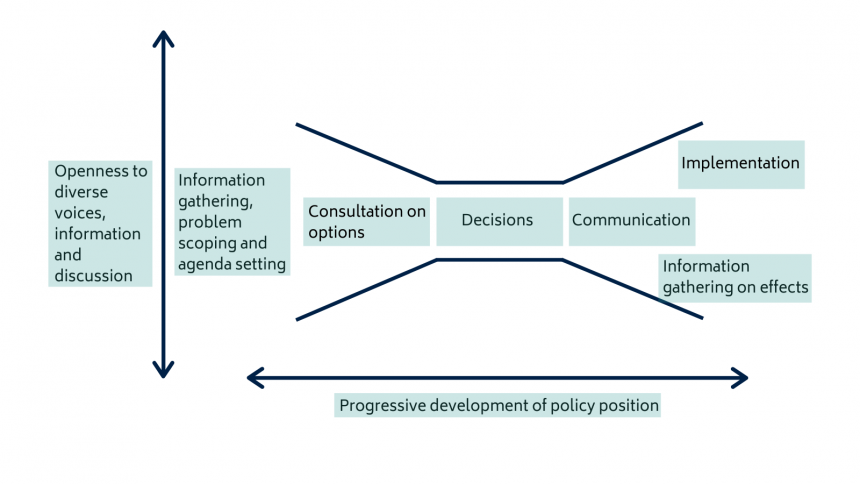

The application of this kind of analysis can potentially be very helpful, first in determining at what point the knowledge they have acquired will add value to the policy process, and secondly in trying to understand where approximately the development of any issue they are interested in may have got to in the process. It is important to bear in mind that, while there are many possible entry-points for engagement and dialogue, there are stages when officials will try actively to resist the entry of new knowledge into consideration. This is not simply obstructiveness or a sign of closed minds; it is the consequence of attempting to manage an inherently chaotic process and drive things forward to the best decision possible in the circumstances. It can be depicted as the deliberate narrowing of a funnel, as suggested in the diagram, where the width of the funnel represents the openness of policy process to diverse voices, actors, and sources of information. (It is this narrowing effect and exclusion of new information which can then later lead to embarrassing episodes of contorted argument to defend the indefensible position officials find themselves and their Ministers in.) After implementation, the funnel narrows again at the time of any evaluation, as evidence is sifted, evaluative judgements made, and confidential discussions held on the most appropriate public response to the findings.

How research evidence contributes to policy: the narrowing of the policy process's openness to diverse voices, actors, and sources of information.

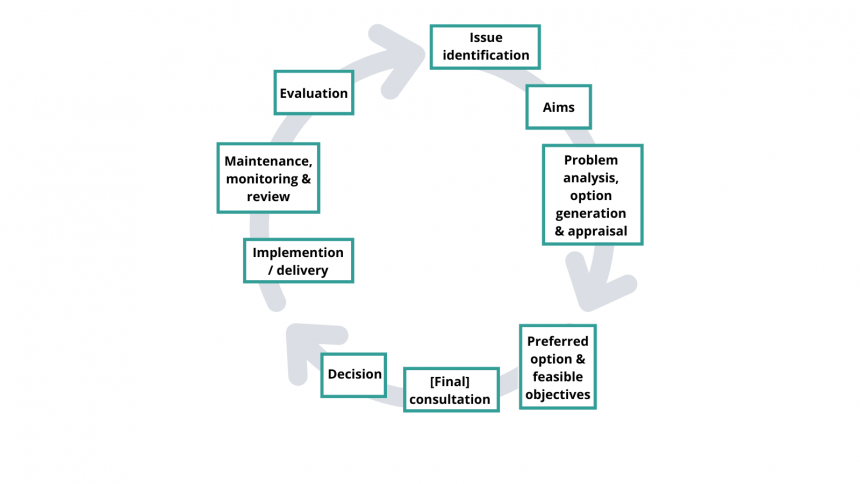

The sequence of policy process phases can also be depicted as a cycle, which provides a useful heuristic device for teaching purposes and also indicates the iterative nature of public policy: few policy initiatives begin with a blank sheet and few ever represent the final word on an issue. There are, again, many different versions of such a cyclical diagram.

A policy cycle: from issue identification and option generation to implementation and evaluation

Such cyclical or sequential representations of policy-making have been unfashionable in the UK for some years, and indeed all are vulnerable to the criticism that they may imply an overly rational, intentional and orderly process. For example, a Cabinet Office report said that “ a model. showing sequential activities organised in a cycle . . . [does] not accurately reflect the realities of policy making . . . policy-making rarely proceeds as neatly as this model suggests and . . . no two policies will need exactly the same development process.”

Building on this, the Institute for Government said: “The issue is not that the model is wrong, but that it is too distant from reality to be useful. . . . it reduces policy making to a structured, logical methodical process that does not reflect reality. Even policies which have the semblance of proceeding in stages actually consist of a series of reversals and repetition. Stages are fused together, get driven by contingencies not logic, and produce diffuse effects that overlap with those from other policy initiatives.”

These are important caveats to keep in mind. All practitioners know that such models are just that – simplifying devices to aid analysis and comprehension – and that policy-making in reality is fraught with complexity, contingency, uncertainty, inadequate data, accident, misunderstandings and political conflict (some of it within government). They are not intended as algorithms, nor do they reflect prescribed procedures. But they do strive to represent the intrinsic logic through which the phases of policy-making can commonly be observed to unfold, albeit with iterative loops, reversals and false starts. At the same time, many case studies of dramatic policy failures show the risks than can materialise when stages are skipped or skimped, whether for reasons of urgency, overwhelming prior political conviction, or simple lack of capacity. Researchers seeking to open up a dialogue with policy officials in government should not expect there to be, at any one time, a clear sense that the response to a particular issue has reached a specific clearly-delineated stage of a defined process; they may, though, find such a visualisation a helpful aid to their own understanding of how, when and where to engage, and with who research findings may gain traction.

Professor Mark Reed describes the experience of policy officials well:

“It is easy to sit on the sidelines and criticise colleagues in the policy community for the many imperfections of real-world policy processes. It is a lot harder to be critical if you have spent any time working in government departments, trying to juggle the multiple competing claims on your time and the curve-balls that get thrown at you by politicians or external events. In addition to synthesising evidence from research, there is the need to balance the interests of different stakeholders and public opinion, and listen to the practitioners who may explain why theory (from our research) doesn’t always translate into practice.”

In addition, it is valuable in any governmental context to try to gain an understanding of the normal internal working practices, determined by habit, convention, assumptions and organisational and cultural norms, within any ministry, department or agency. These micro-processes, as much any formally determined procedure, will to a large extent determine how information (including research knowledge, gets into the policy process. The interested observer might try to take note of who asks or instructs whom to do what, and how prescriptively, and who does what on their own initiative. For example, would a senior official more typically direct a junior which resources to use when preparing a draft, point them to a particular external source of advice to consult or to commission to carry out a task, or simply ask them to investigate an issue? Developing an understanding of these practices can greatly help in knowing with whom and in what way researchers might productively seem to establish a dialogue. Such an understanding will be greatly aided by a long-term relationship with the organisation and immersion in its work, but the World Bank’s Bureaucracy Lab is producing some useful findings about the internal workings of governments across the world.

Understanding the policy process comes down in the end mainly to an appreciation that it is infinitely variable and contingent, that this interplay of factors is happening, and that it is essential to be responsive to this, to work within this complex system and its emergent features, and to try to sense how the dynamics are playing out.

One final word: despite the title of this guidance note, attempting to understand in any specific context how the multiple factors affecting policy making will interact with one another is probably a fool’s errand. Understanding the policy process comes down in the end mainly to an appreciation that it is infinitely variable and contingent, that this interplay of factors is happening, and that it is essential to be responsive to this, to work within this complex system and its emergent features, and to try to sense how the dynamics are playing out. And in the middle of all this one will usually find policy officials who are hugely task-oriented, and driven to get the job done to the satisfaction of their superiors and political masters.