Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Peruvian highlands were home to the largest empire in the Americas. From their capital Cuzco, in modern-day Peru, the Incas controlled large swaths of territory that spanned Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Although the area fell to Spanish conquistadores nearly five centuries ago, traces of the Inca Empire remain, most recognizably at Peru’s many majestic archeological sites. But the Incas left Peru more than physical remains. Even today, in some regions of the country, Quechuan and Aymaran languages—the former, the main language family of the Inca Empire; the latter, its close relative—are spoken more than any other.

Speakers of those and other Indigenous languages continue to figure prominently in Peru today. Indigenous Peruvians make up more than a quarter of the population and have, at times, wielded significant political power. Peruvians elected the country’s first Indigenous president in 2001. Twenty years later, the nation’s Indigenous communities voted their preferred candidate into office again.

But more often, Indigenous Peruvians have found themselves excluded from the halls of power. Compared with the country’s White and Mestizo communities, Indigenous Peruvians, who often live in remote, rural regions, suffer disproportionately from poverty, malnutrition, and illiteracy, a result of centuries of discriminatory practices. They also lack access to high-quality education and many of the social services available in the country’s more affluent urban districts.

The plight of Indigenous communities is one of the largest challenges facing Peru and its educational system today: entrenched inequality that divides the city from rural areas, the rich from the poor, and the Indigenous from the White and Mestizo. While economic development helped reduce some of the country’s wealth and educational disparities, recent reversals have made it clear just how hard it will be to root out the problem. Mustering the political will needed to address these disparities will be key to Peru’s future prosperity and well-being.

Until recently, it seemed that strong economic growth alone could fix inequality. Fueled by rising raw material and mineral exports—the country today is one of the world’s largest producers of copper, silver, and zinc—Peru’s economy began to take off around the start of the twenty-first century. Nearly every year since, the country’s economic growth rate has outpaced world and regional averages, making the economy one of Latin America’s fastest growing.

This economic growth had a profound effect on Peru’s population. Since the expansion began, Peru’s Gini coefficient, a measure of the country’s income inequality, has fallen steadily. At the same time, the ranks of the middle class have swelled. In 2018, the Lima Chamber of Commerce (CCL) classified almost 45 percent of the population as middle class, 1 up from just 17 percent in 2004. More importantly, Peru’s growing economic prosperity has lifted millions out of poverty. Between 2008 and 2018, the proportion of Peru’s population living in poverty fell from 37 percent to 21 percent.

But the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the fragility of this progress. Despite early and aggressive lockdowns, infections in Peru quickly spiraled out of control, overwhelming the country’s health care system. The results have been tragic: Peru’s per capita death toll is the highest in the world.

The severity of the outbreak has also depressed Peru’s economy which, because of its reliance on resource exports, was always particularly vulnerable to demand shocks. The World Bank estimates that Peru’s gross domestic product (GDP) declined by about 12 percent in 2020, one of the sharpest contractions in the world.

Like disadvantaged people in other countries, Peru’s underprivileged populations have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s health and economic toll. Alarmingly, the health crisis seems to have reversed much of Peru’s progress in combating poverty over the last two decades. Since the outbreak, the percentage of the population living in poverty has expanded considerably, growing from around 20 to 30 percent.

Political instability hindered a more effective COVID-19 response. In November 2020 alone, the country went through three different presidents. The lack of stability may also limit the government from tackling inequality after the pandemic ends.

Peru has a long history of political unrest. Since declaring its independence from Spain in 1821, Peru has gone through 12 different constitutions. The latter half of the twentieth century was especially calamitous, as authoritarian rule and armed conflict violently upended the lives of countless Peruvians. The events of these years continue to impact the nation today. Measures are still in place to compensate the victims of the violence and destruction unleashed by both sides during the government’s armed conflict with the Maoist guerrilla movement, the Shining Path, between roughly 1980 and 2000.

More recently, corruption has helped spark political turmoil. The country’s notorious strongman, Alberto Fujimori, president from 1990 to 2000, is currently serving a 25-year prison sentence for human rights abuses, corruption, embezzlement, and bribery. Since his sudden resignation and flight to Japan in 2000, seven more Peruvian presidents have been investigated, impeached, or imprisoned on allegations of corruption—in 2019, one even committed suicide after a warrant was issued for his arrest. Unsurprisingly, in 2020, Peruvians named corruption the country’s most worrying problem, well ahead of the next two most cited issues, insecurity and poverty.

Corruption also played a major role in the country’s most recent burst of political upheaval. In early November 2020, lawmakers impeached and removed then-president Martín Vizcarra, whose actions in office broke the mold of the country’s recent leaders. Although charged with “permanent moral incapacity,” many outside observers believe that his anti-corruption initiatives may have been more damning—at the time of his impeachment, 68 legislators were under investigation for a variety of offenses.

Vizcarra’s ouster sparked immediate outrage. Even with the pandemic raging, demonstrations broke out in towns and cities across the country, forcing the interim president to step down after just six days in office. Protests continued in the ballot box a little less than six months later, when Peruvians elected Pedro Castillo, the nation’s first left-leaning president since 1975, delivering what The New York Times described as the “clearest repudiation of the country’s establishment in 30 years.” In the election, Castillo, a political outsider and former elementary school teacher, narrowly defeated Keiko Fujimori, daughter of the former strongman and one of the long-ruling political class’s most prominent representatives—like many of them, she faces her own set of corruption charges and up to 30 years in prison.

Backing Castillo were Peru’s Indigenous communities, inspired by his promise to tackle the disparities that have left the country’s rural areas behind. But while the election of Castillo, who took office in July 2021, represented a definitive break with the political status quo, with Congress still dominated by the opposition his first few months in office have proved chaotic and raised serious doubts about his ability to fulfill his campaign promises.

Peru’s education system mirrors these political and economic developments. Like the nation’s economy, it, too, especially the higher education sector, has expanded rapidly over the past two decades. Between 2008 and 2018, enrollment in Peruvian higher education institutions grew faster than in any other country in Latin America, more than doubling from around 775,000 to 1.6 million. Universities grew at a similar rate: Between 2000 and 2019, the number of active universities increased nearly twofold, growing from 74 to 139.

But this expansion has not been without its challenges. To meet growing demand, the government until recently subjected universities to minimal interference and supervision, creating a policy environment that allowed low-quality for-profit institutions to thrive. The rapid expansion of these institutions has since made it difficult for the government to address quality challenges—the recent adoption of more stringent quality assurance mechanisms prompted the government to close institutions attended by nearly a quarter of the student population.

The expansion of Peru’s higher education system has also occurred unevenly across the country. Despite recent improvements, wide disparities in learning access and outcomes remain between urban and rural districts and rich and poor Peruvians. Progress has been especially slow for members of Peru’s many Indigenous communities.

The pandemic has further complicated these challenges, revealing the fragility and imbalances of recent progress. While Peru’s early decision to suspend in-person classes at the country’s schools and universities likely helped to slow the spread of the virus, it also deepened already profound educational disparities. According to data from Peru’s National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, INEI), at the start of the pandemic just 36 percent of households had a computer and 40 percent had access to the internet. In rural areas, where educational access and outcomes were limited even before the pandemic, the situation is especially dire. In 2020, while 63 percent of households in Lima, the country’s capital and largest city, had access to the internet, only 6 percent of rural households did.

As a result, large numbers of students—likely those from poor and rural families—have been forced to drop out. Reports indicate that Peru’s high school and university dropout rates, both around 12 percent in 2019, have risen swiftly since the start of the pandemic, growing to 18 and 19 percent, respectively, in 2020. With distance-learning continuing at most schools and universities in 2021, those numbers are likely to rise.

The government has responded by distributing tablets and developing radio- and television-based education programs. Peru’s dedicated teacher workforce has also adopted creative approaches to reach students in areas with limited internet access. Still, observers worry that for Peruvians forced to end their education early, many of whom are likely to be among the country’s most vulnerable, the educational consequences of the pandemic will be severe and long-lasting.

But even those able to continue their education could face daunting prospects after graduation. In 2019, long before the COVID-19 outbreak, less than half of all Peruvians with at least a secondary school certificate between the ages of 18 and 29 were working, studying, or training, according to data from INEI. And among those lucky enough to find employment, working conditions were often precarious. A report from 2018 notes that among employed youths, seven out of ten lacked health insurance, were underemployed, or received low wages.

The government has long recognized the challenges facing graduates of the country’s schools and universities and, in recent years, has introduced ambitious reforms aimed at improving educational quality and employment outcomes. Among the most significant are measures that raise university licensing standards to address the quality issues arising from the rapid proliferation of private universities and mandate a reassessment of program content to address mismatches between education and the labor market.

As the world continues to gradually recover from the coronavirus pandemic, these reforms, and projections suggesting that Peru’s economy will bounce back soundly, do leave some room for optimism. However, the nation, as well as its education system, will still need to grapple with significant challenges, most notably its widespread socioeconomic and regional inequality and the very real threat of political turmoil and economic volatility. Given the deep roots of these challenges, it’s unclear whether any of the changes made to date—in the political or educational sphere—will be enough to overcome them.

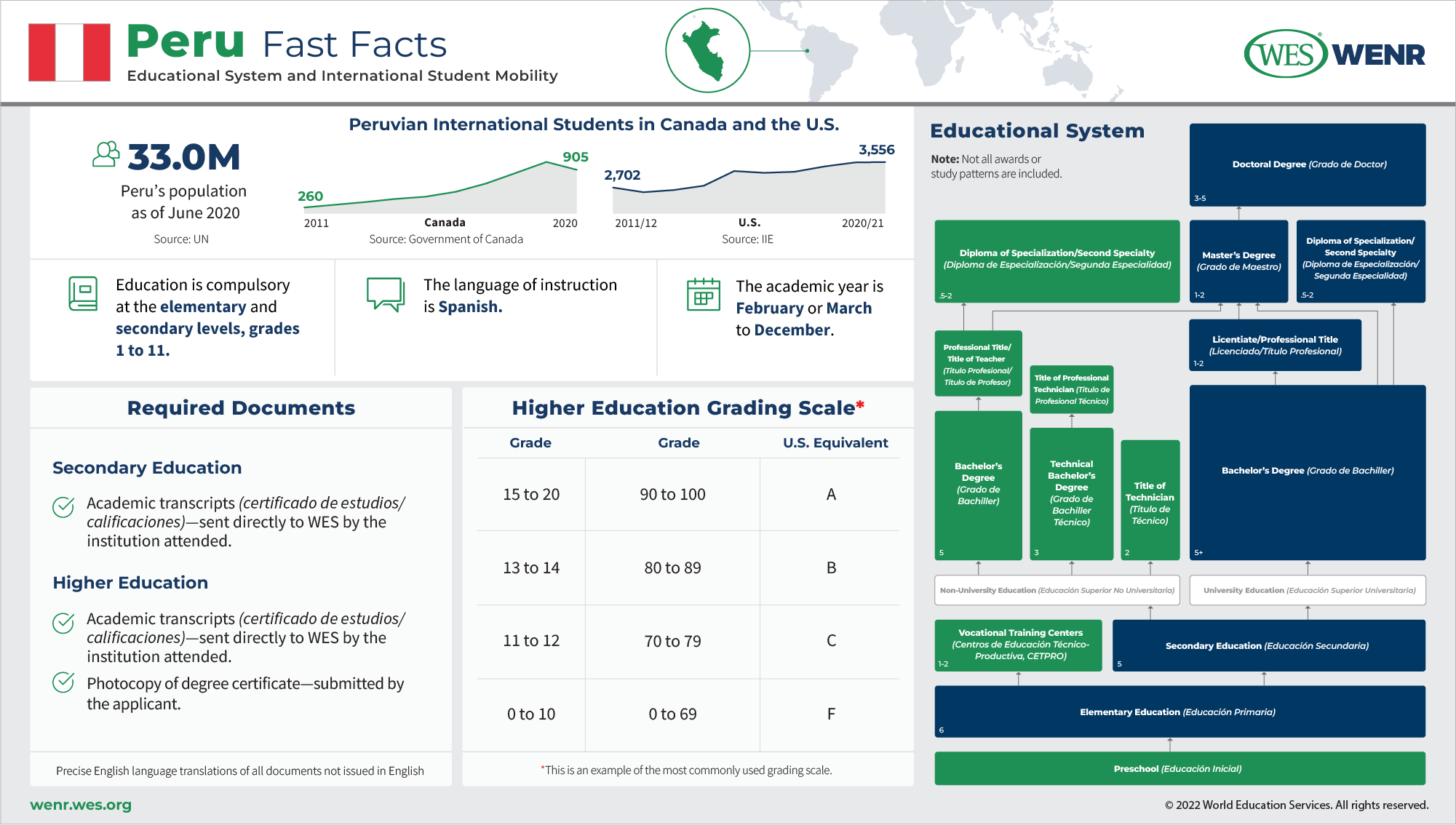

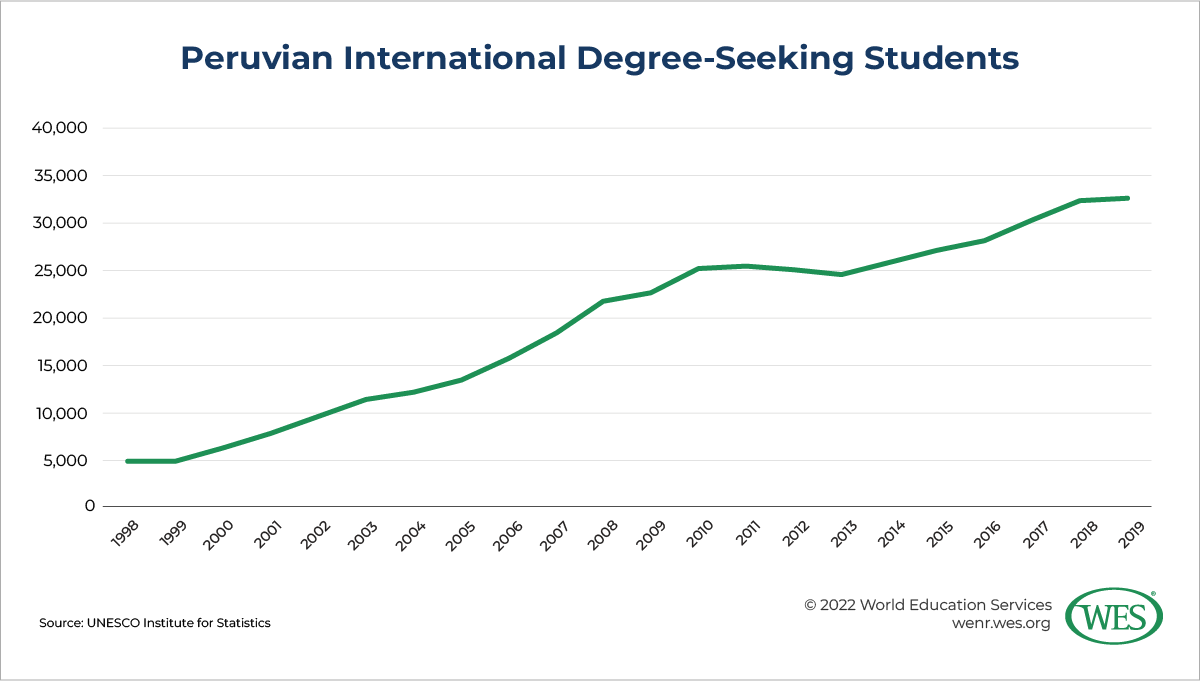

Driven by its rapidly expanding middle class, Peru over the past two decades has grown into a significant source of international students. Just the 72 nd- largest source in 1998, when the country sent 5,900 international degree-seeking students abroad, by 2019 it was the 38 th- largest, with 33,837 Peruvian students studying overseas, according to data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Among other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), Peru sends the fourth-largest number of students abroad, behind only Brazil (81,882), Colombia (52,064), and Mexico (34,319).

Government policies and funding have helped boost this mobility. In recent years, the government of Peru, often through the Programa Nacional de Becas y Crédito Educativo (PRONABEC), a public agency attached to the Ministry of Education, has funded a number of different overseas study scholarships as a means of meeting the country’s development goals. Among the most important is the Bicentennial Generation Scholarship, known as the Beca Presidente de la República prior to 2021. Established in 2012, the scholarship currently funds master’s and doctoral studies in critical fields, such as education; public policy; and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), at top global universities. 2

Until the last several years, the government offered an even greater variety of international study scholarships, such as the Reto Excelencia, which helped public servants study overseas. However, more recently, the government has refocused its funding efforts on in-country scholarships for high-performing or disadvantaged Peruvian students.

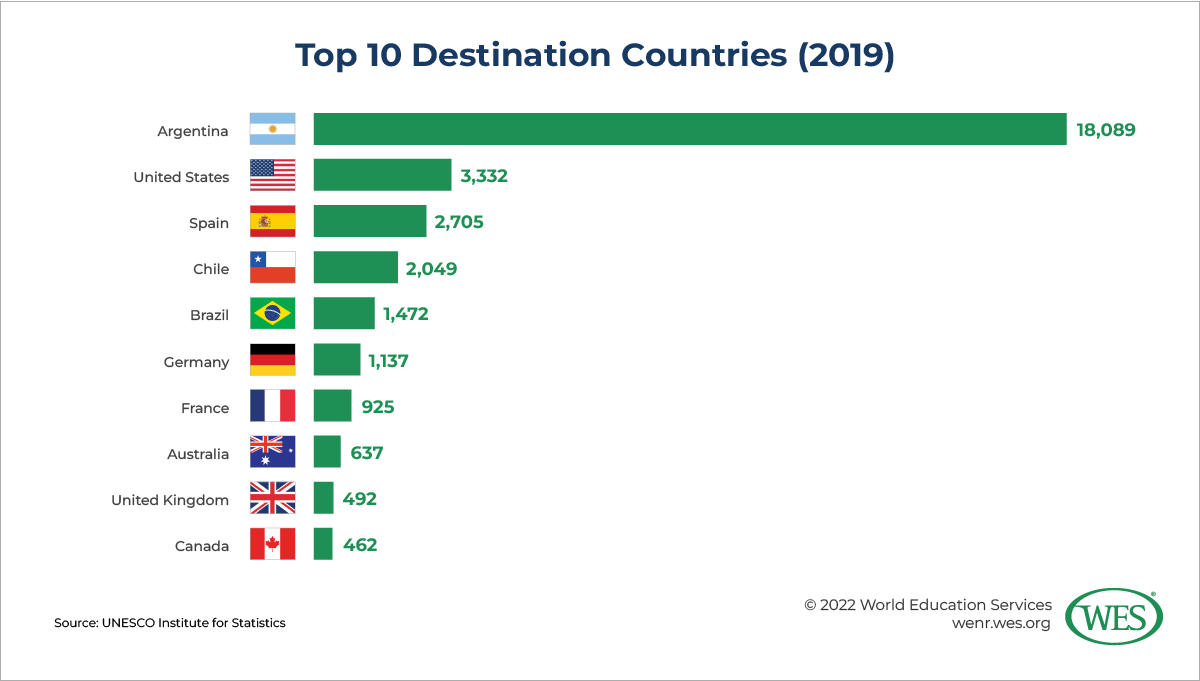

Unlike international students from most other LAC countries, those from Peru typically stay close to home. While a 2019 study from the UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean revealed that just 38 percent of international students from LAC countries stay within the region—well below rates in other regions worldwide—around two-thirds of all Peruvian international degree-seeking students enroll in other LAC countries.

More than half (53 percent) of all Peruvian international students—18,089 in 2019 alone—enroll in just one LAC country: Argentina. They’re not alone. Argentina is by far the region’s most popular international study destination, attracting 116,330 total students in 2019, or nearly half of all international students studying in LAC countries, according to UIS data.

Peruvian students are likely drawn to Argentine universities by their comparative high quality, their lack of admissions examinations, and, at least at public institutions, their free tuition, even for international students. The last point is likely important: Around 80 percent of Peruvian international students in Argentina enroll in public universities.

Peruvian international students remain quite cost conscious. Intead’s Fall 2019 Know Your Neighborhood report revealed that affordability, selected by 62 percent of survey respondents, was the most important factor influencing Peruvian student decisions of where to study in the United States. That rate, among the highest in South America, likely reflects economic conditions at home. Despite the country’s growing prosperity, Peru’s per capita gross national income remains lower than that of other large Latin American countries like Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

Ambitious Peruvians are likely also drawn to Argentina by its top-notch academic institutions. Among its most prominent is the University of Buenos Aires, Latin America’s top-ranked university and, according to the 2022 QS World University Rankings, among the top 100 universities in the world. The massive public university enrolls over 300,000 students, a large number of whom are international. By comparison, Peruvian universities tend to fare far worse in international rankings, and competition for the relatively limited number of seats at high-quality universities can be fierce.

Regional initiatives could make Argentina—and other popular LAC countries like Chile (2,049) and Brazil (1,472)—even more attractive to Peruvian students in the coming years. In July 2019, 23 LAC countries, including Peru, adopted the Regional Convention on the Recognition of Studies, Diplomas and Degrees in Higher Education, which seeks to “advance and boost academic mobility, in order to increase access to education.” Bilateral visa-free agreements, such as the one with Mexico, have also facilitated intraregional mobility. Inter-institutional student and faculty initiatives, such as the Programa Pablo Neruda de Movilidad Académica and those run by the Consejo de Rectores por la Integración de la Subregión Centro Oeste de Sudamérica (CRISCOS), have also helped promote international student mobility between member institutions.

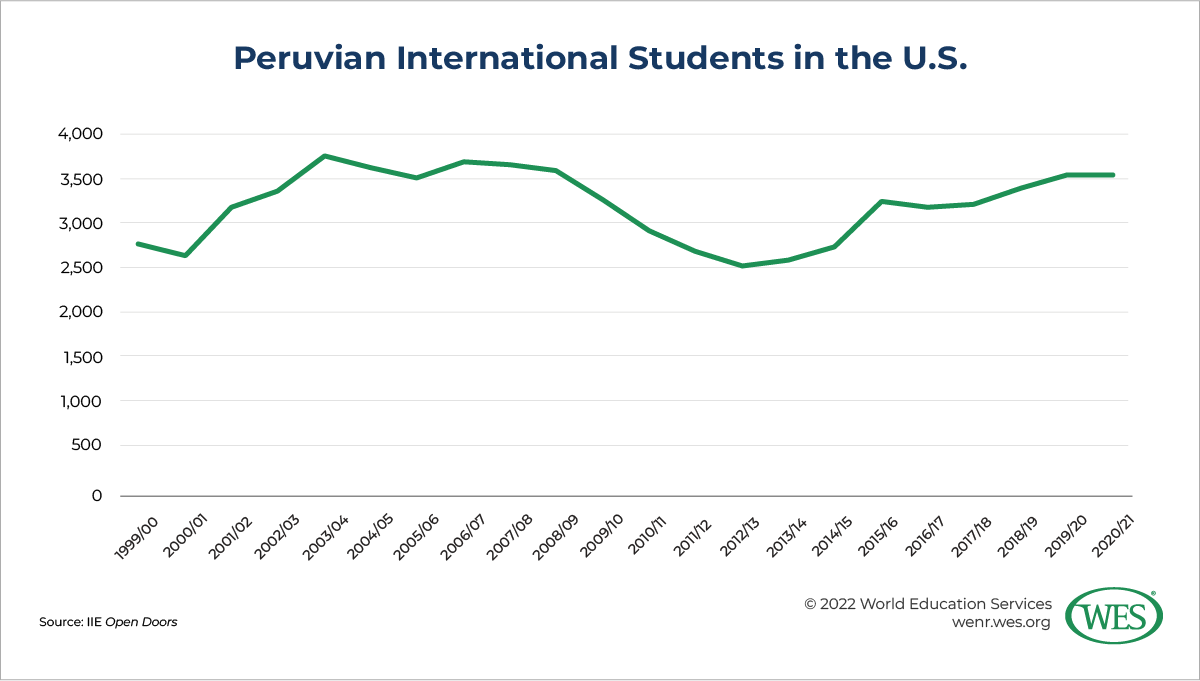

After Argentina, the U.S. is the second most popular destination for Peruvian international students. According to the Open Doors report of the Institute of International Education (IIE), 3,556 Peruvian international students were enrolled in the U.S. in the 2020/21 academic year. 3 Although that number is significantly higher than in 2012/13, when the effects of the Great Recession drove Peruvian enrollment down to 2,539, it remains slightly below the levels reached in the mid- to late 2000s.

Still, observers continue to predict that the number of Peruvian students studying in the U.S. will rise in the coming years. One reason for their optimism is the government’s commitment to a policy of bilingualism, through which it hopes to familiarize all children with a foreign language, English in particular. Given the difficulty that many Peruvians have with English—the 2020 EF English Proficiency Index assessed Peru’s average English proficiency as low, ranking it 59 of 100 countries—many expect this focus to eventually boost enrollment in Anglophone countries.

Of those Peruvians who do choose to study in the U.S., a plurality enroll in undergraduate programs (47 percent), followed by graduate (31 percent), and non-degree (7 percent) programs. The Optional Practical Training (OPT) program has grown increasingly popular among Peruvian students in recent years, as it has with students of other countries. In 2019/20, 15 percent of Peruvian international students in the U.S. were enrolled in OPT, up from 7 percent in 2006/07.

Intead’s Fall 2019 Know Your Neighborhood report, mentioned above, revealed that most prospective Peruvian international students were interested in programs in business and management (32 percent) and STEM (29 percent) fields, including 17 percent who were interested in engineering. The report also suggested that nearly a quarter (24 percent) were interested in English language programs.

Canada has seen far more rapid growth in recent years. In the decade preceding 2019, Peruvian enrollment in Canadian universities grew around 325 percent, although the COVID-19 pandemic caused enrollments to decline 13 percent to 905 students in 2020, according to government statistics.

Given the importance of cost to many Peruvian students, the low tuition fees of many Canadian universities—at least compared to those of U.S. universities—are likely an important draw. Canada’s comparatively friendly visa and immigrant policies likely also play a role. That policy attitude has largely survived the pandemic: In July 2021, Canada expanded eligibility for its Student Direct Stream, a fast-track student visa processing scheme, to include Peruvian students.

Inbound mobility numbers for Peru are less forthcoming—the government does not appear to report inbound international student numbers to UIS. Still, given the limited popularity of other LAC countries to global students—the region hosted only a little more than 239,769 in 2019, or around 4 percent of the global total—it seems unlikely that Peru is a major destination for international students.

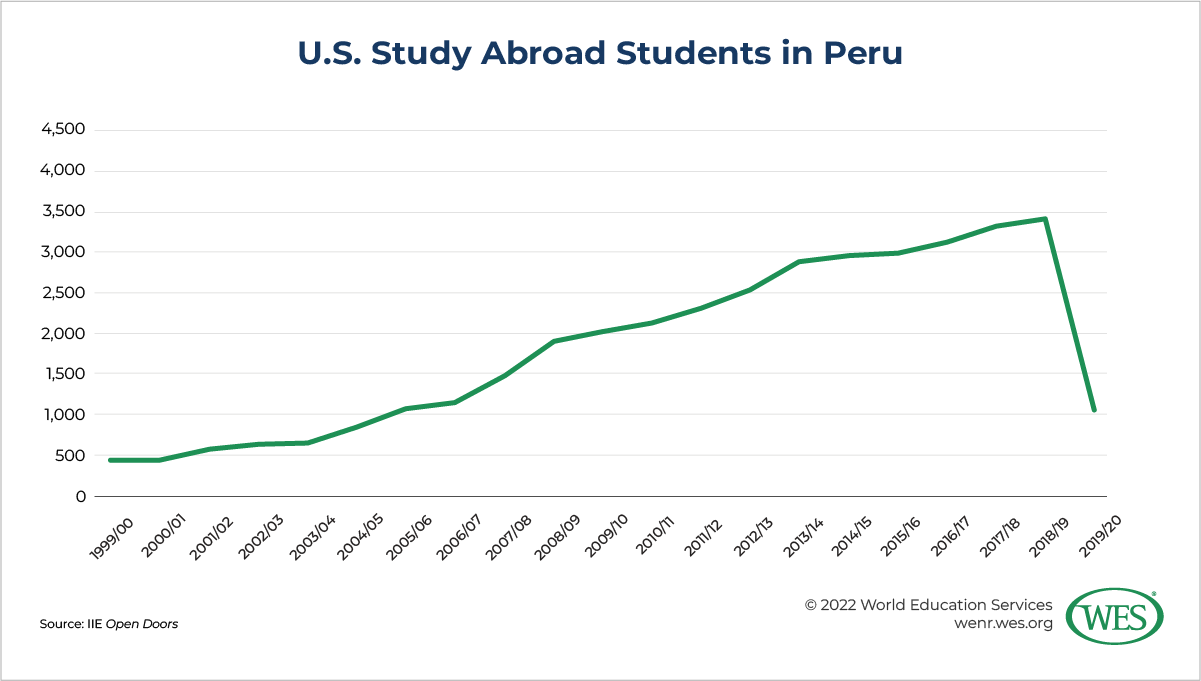

Despite this lack of globally comparable data, there may be reason to believe that Peru is beginning to attract more international students. In the two decades preceding the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of U.S. study abroad students—whose short-term overseas studies wouldn’t be included in UIS data in any case—choosing to study in Peru has grown considerably. Between 1999/00 and 2018/19, the number studying in Peru increased more than 10-fold to reach 4,041, according to IIE Open Doors data. As a result, in 2018/19, Peru was the third most popular destination among LAC countries for U.S. study abroad students, trailing just Costa Rica (6,340) and Mexico (8,333). 4

Over that time, growth in study abroad in Peru far outpaced that of its regional neighbors. In 1999/00, just 7 percent of all U.S. study abroad students in South America and 2 percent of those in LAC countries were studying in Peru. By 2018/19, those percentages had grown to 22 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

Peru’s growing prosperity and improved security situation likely set the stage for this growth. Over roughly the same period, the number of tourists—a notoriously comfort-sensitive demographic—visiting Peru also skyrocketed.

While this expansion bodes well for Peru’s future as an international education destination, recent events suggest that it could prove fleeting. Peru’s inability to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, despite strict lockdowns, led to a collapse in study abroad numbers. In 2019/20, enrollment declined by 72 percent, a rate much faster than in other South American (-57 percent) and LAC countries (-55 percent). As illustrated by the way Peru has handled the pandemic, the country’s ability to attract international students likely hinges on its still fragile economic and political order.

The Incas established the first historically recorded education system in what would eventually become Peru. Restricted to the sons of the nobility of both the Incans and their conquered subjects, Incan formal education lasted four years and was conducted by amautas, or polymath scholars, in yachay wasi, or houses of learning. There, Inca youths learned the skills needed to run the empire’s sophisticated administration. They studied the Quechua language; religion and ritual; accounting through the use of quipu, or knotted strings; and history—as well as a smattering of sciences, including astronomy; geography; and geometry. At the end of their studies, they were subjected to a series of examinations, success in which was necessary to enter the Incan civil service and take one’s place as a full member of the nobility.

This system came to an end with the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in the sixteenth century. During the nearly three centuries of colonial rule that followed, the Catholic Church played the leading role in the country’s education. In 1551, less than a decade after the formation of the Viceroyalty of Peru, the church established the first university in the Western Hemisphere in Lima, the new colonial capital. Today that university is known as the National University of San Marcos. But Catholic education, like the Incan system it supplanted, was still largely reserved for the privileged few, aimed at preparing the Viceroyalty’s Spanish elite for leadership roles in the colonial administration and the church. All but excluded from the formal education system, the Indigenous population continued to rely on oral traditions to preserve and transmit traditional knowledge until well after Peru’s independence from Spain.

Only after independence and the formation of a modern state did Peru’s government begin to wrest control of education away from the church and expand access to broader segments of society. In 1837, the Peruvian government established the country’s first education ministry which assumed progressively wider responsibility for administering and financing education in the decades that followed.

Although steady progress was made in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that a large-scale expansion of the education system took off. In the 1940s, the government made elementary education compulsory while also allocating additional funds to train teachers, develop school infrastructure, and expand the network of secondary schools. As a result, between 1958 and 1968, education enrollments nearly doubled. Still, high dropout rates persisted: 9 out of every 10 students enrolled in elementary education did not go on to complete secondary education.

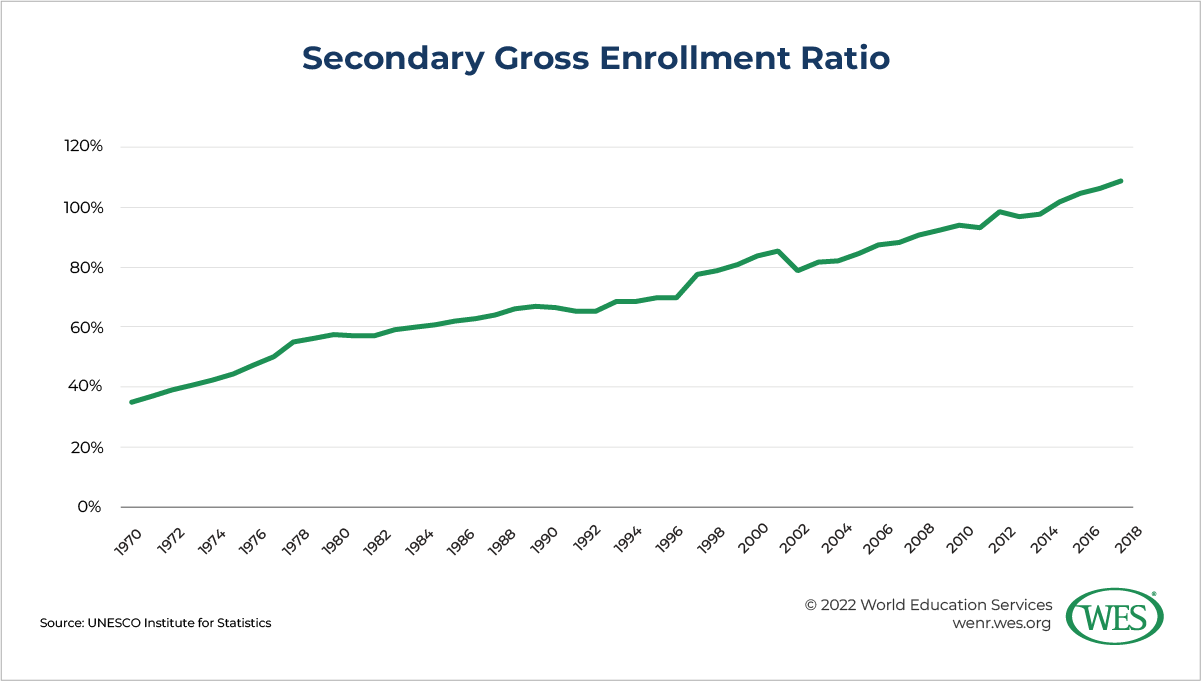

In fact, secondary education has only recently been extended to the entire population. According to UIS data, Peru’s secondary gross enrollment ratio (GER) increased from around 35 percent in 1970, to 81 percent in 2000, to 111 percent in 2020. Unsurprisingly, literacy rates have also skyrocketed, growing from 82 percent of the adult population in 1981 to nearly 95 percent in 2019.

Still, disparities continue, and learning access and outcomes vary widely by geographic location, socioeconomic status, and gender. For example, while government data show that the illiteracy rate was just 3 percent for adult males nationwide in 2019, it was 8 percent among females. When contrasting men and women from different geographic areas, disparities are even more stark. Only 2 percent of men living in urban areas were classified as illiterate in 2019. Among women living in rural areas, nearly a quarter (23 percent) were.

Extending access to impoverished, Indigenous, and remote communities remains an especially persistent challenge. For example, the country’s highest illiteracy rates are in the isolated regions of Apurímac and Huancavelica, where Quechua or Aymara—both of which are widely spoken, but rarely written—are the first languages of roughly two out of every three residents. Similarly, in the affluent, more urbanized regions of Arequipa, Moquegua, and Madre de Dios, the upper secondary net enrollment ratio exceeded 90 percent, while in Ucayali, Loreto, and San Martin regions, all located in the Peruvian Amazon rain forest, rates ranged from 73 to 80 percent. Similar disparities, discussed below, exist at the higher education level as well.

While government efforts, such as the expansion of intercultural bilingual education, have managed to narrow some of these gaps in recent decades, meeting the needs of underprivileged communities is likely to remain a challenge for years to come.

The Republic of Peru, as it is officially known, comprises 26 principal administrative divisions, including 25 regions (24 departments and the Constitutional Province of Callao) and Lima Province. The latter, although geographically one of the 10 provinces that make up the Department of Lima, is an autonomous administrative entity and is often considered separately from the rest of the department for statistical purposes. Lima Province is also the seat of the country’s capital and largest city, Lima, which is home to nearly 10 million people, or around 30 percent of Peru’s total population.

These departments and provinces form the focal point for the nation’s ongoing decentralization initiatives, first introduced in 2002, which aim to transfer a number of powers to popularly elected regional governments. In the years since, Peru’s Congress has passed a number of measures expanding and further defining the authority of regional governments and institutions. They have also introduced provisions aimed at redrawing regional boundaries in an attempt to address concerns that the current regions are too small to be financially viable. A law passed in 2004 provides for the consolidation of existing regions to create larger territorial units and taxing jurisdictions able to provide regional governments with the funds needed to assume an expanded set of responsibilities more closely resembling those of state governments in the U.S. or provincial and territorial governments in Canada. Although the government has attempted to incentivize these mergers by granting the consolidated regions a share of national sales, consumption, and income taxes, as of 2021, no new regional governments had been formed.

When or if they do form, these new, enlarged regions will need to merge their respective education departments. Since the nation began its decentralization push, the central government has introduced reforms aimed at gradually transferring many of the responsibilities of the central Ministry of Education (Ministerio de Educación, MINEDU) to the education departments of regional governments (Direcciones Regionales de Educación, DRE) and other lower level administrative units. When fully implemented, these reforms, first outlined in the still-current 2003 Education Law, will give DREs more control over educational administration, planning, curriculum development, and quality control, giving them a role that more closely resembles that of regional or state governments in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico.

Still, despite some progress, the process of decentralizing education has been slow. Responsibility for the recognition of foreign study and the authorization of private institutions was only transferred to DREs recently, in 2016 and 2019, respectively, while the planned devolution of many other MINEDU responsibilities has yet to begin. Education isn’t the only sector where the reforms have stalled. Minimal progress has been achieved across the board, leaving many Peruvians pessimistic about the prospects of full decentralization.

As a result, the central government, largely through MINEDU, continues to play an important role in administering all levels of the education system. At the elementary and secondary levels, MINEDU retains primary responsibility for funding, determining school calendars, setting the national curriculum, designing and distributing textbooks, monitoring teacher training, and establishing salary schedules for teachers and school administrators.

MINEDU retains similar responsibilities for education at the post-secondary, non-university level (educación superior no-universitaria), which is one of two subdivisions of educación superior (which can be translated as either post-secondary or higher education). Post-secondary, non-university education is further divided into higher technological, teacher, and art education (educación superior tecnológica, educación superior pedagógica, and educación superior artística).

In recent years, a number of laws and ministerial resolutions aimed at improving quality and better integrating university and non-university qualifications have significantly altered the post-secondary, non-university landscape. These reforms have both expanded the academic, administrative, and financial autonomy of non-university institutions and tightened the rules regulating their creation, management, and quality assurance. They have also significantly raised licensing standards. Given the quality issues plaguing much of the sector, the latter move has led observers to expect that many institutions will struggle to remain open.

Institutions at the university level (educación universitaria), the other subdivision of educación superior, enjoy a greater degree of autonomy than their non-university counterparts. Since 2014, when the current University Act was passed, they have also been overseen by a different state body, the newly created Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Superior Universitaria (National Superintendence of University Education, SUNEDU). SUNEDU, an agency attached to MINEDU, is responsible for policy development and quality assurance in the tertiary university system.

Central government spending, which finances public schools and universities and a number of need- and merit-based scholarships, has gradually increased in recent years. Between 2011 and 2019, government expenditure on education as a percentage of total GDP increased from around 2.7 to 3.8 percent. Still, government spending in Peru trails that of its regional neighbors, at times by significant margins. In 2019, average public spending among all LAC countries was 4 percent, while other large South American countries like Brazil (6 percent in 2018), Chile (5.4 percent in 2018), Argentina (4.8 percent), and Colombia (4.5 percent) spend even more.

Peru’s 2003 Ley General de Educación defines two main levels of education: basic education (educación básica) and higher, or post-secondary, education (educación superior). By international standards, elementary and secondary education—both subdivisions of basic education—are relatively short, lasting just 11 years, from age 6 to 16 or 17. All years are compulsory. According to Peru’s constitution, early childhood education is also compulsory, although that requirement does not seem to be regularly enforced.

The language of instruction for both basic and higher education is usually Spanish, although Indigenous and foreign languages are taught and used in certain schools and programs. The academic year at all levels typically mirrors that of other countries in the Southern Hemisphere, running from late February or early March to December.

Basic and higher education are subdivided as follows:

Early childhood education (ECE), or educación inicial, is subdivided into two cycles: one for children between the ages of 0 and 2 and another for those between 3 and 5. According to Peru’s current constitution, adopted in 1993, one year of ECE is compulsory and available free at public schools, although reports suggest that enforcement of this constitutional provision has been lax.

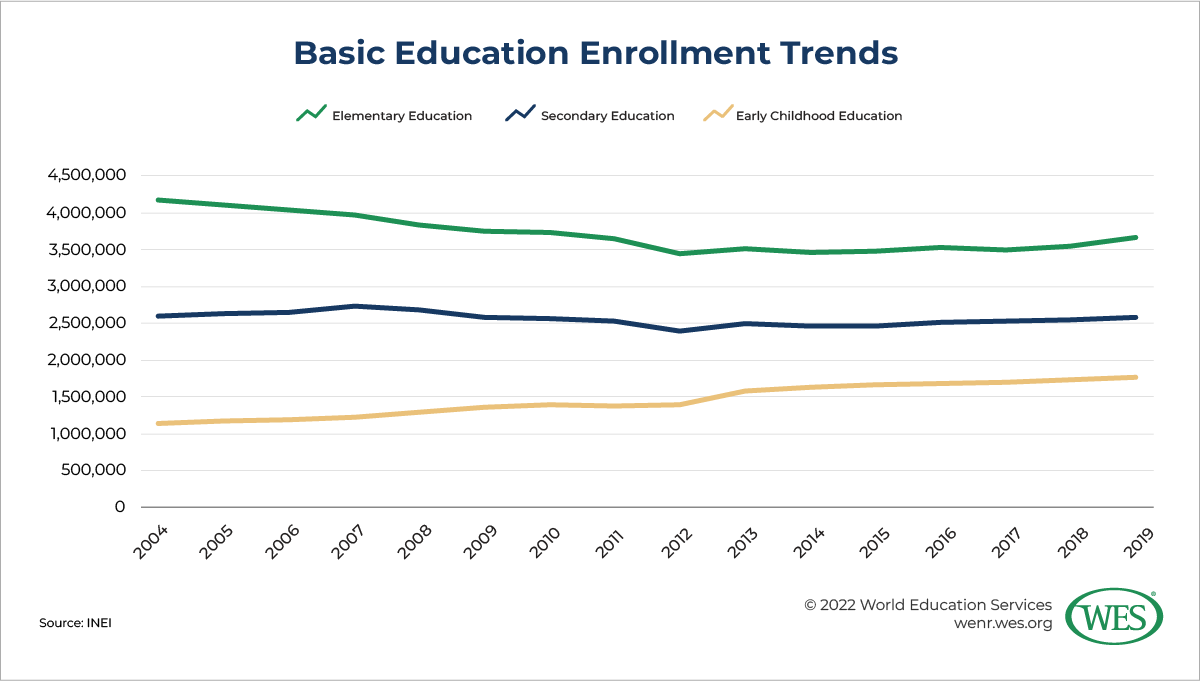

ECE is the only stage of basic education that has witnessed strong enrollment growth in recent decades. Between 2008 and 2019, ECE enrollment grew by 37 percent to around 1.8 million. Over that time, the net attendance rate of children between the ages of 3 and 5 increased from around 66 percent to 83 percent. This growth has been accompanied by a significant increase in government funding. Over the past decade, government spending per preschool student nearly doubled.

Most children enroll in public institutions which accounted for 72 percent of total enrollments, or nearly 1.3 million children, in 2019. Still, demand has far exceeded the supply of public school seats, and enrollment growth in private institutions has well outpaced that in public. Between 2008 and 2019, while enrollment at public ECEs grew by about 30 percent, private ECE enrollment increased by 59 percent to a little under half a million students.

Elementary education (educación primaria) is six years in length (grades 1 through 6) and is subdivided into three two-year cycles. All six years are compulsory, with children generally enrolling in the first grade at the age of six. The national curriculum includes nine learning areas: arts and culture, communications, English as a foreign language, mathematics, physical education, religion, science and technology, social sciences, and the Spanish language. Religion is offered in line with a long-standing agreement between Peru and the Vatican and is not compulsory.

Upon completing grade 6, graduates are awarded the Certificate of Primary Education (Certificado de Educación Primaria). There are no final graduation examinations.

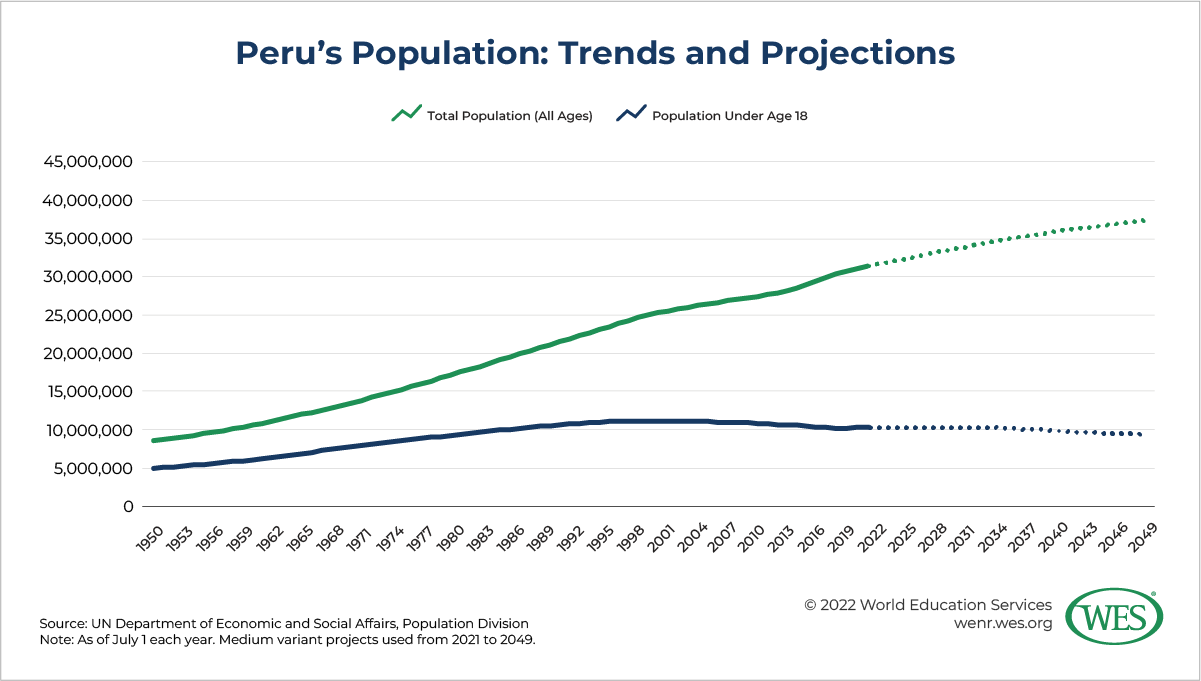

While Peru’s elementary net enrollment ratio (NER) has remained at or above 98 percent since the start of the twenty-first century, overall enrollment levels have declined. In 2019, about 3.7 million Peruvians were enrolled in elementary education, 12 percent less than in 2004, according to INEI data. This decline mirrors the country’s demographic trends. Peru’s birth rate has been falling for over half a century. Although the country’s overall population continues to grow, since peaking at 10.8 million in 2000, the number of Peruvians under the age of 18 has declined by 11 percent, to 9.6 million in 2020, according to data from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Most Peruvian elementary students—nearly three-quarters in 2019—enroll in public schools, which are administered by local management units (Unidades de Gestión Educativa Locales, UGEL) overseen by DREs. An even higher proportion attend elementary schools that teach a general, Spanish language curriculum—in 2019, just one in five attended a school using an intercultural bilingual curriculum, which provides instruction in both Indigenous languages and Spanish. Educational outcomes at these latter schools, which are often located in rural or remote locations, typically lag behind those at schools using a conventional Spanish language curriculum. However, even at the national level, Peruvian learning outcomes, as measured by international examinations, often trail those of their regional counterparts.

Secondary education (educación secundaria) is five years in length (grades 7 to 11) and is structured in two cycles, both of which are compulsory. The first cycle lasts two years, during which all students study a general academic curriculum; the second cycle lasts three years and is divided into academic and vocational streams. There are also four-year secondary education programs for adults who never completed their secondary education, or youth unable to attend secondary school full-time (such as those in rural communities who need to work at home).

Students successfully completing secondary school receive the Certificado de Estudios de Educación Secundaria (Secondary School Certificate). Secondary school graduates are eligible for admission to both university-level and non-university-level post-secondary institutions.

Despite decentralization plans, Peru’s secondary school system remains one of Latin America’s most centralized and homogeneous. Public and private schools throughout the country must follow a national curriculum developed by MINEDU, although officials at the school, local, and regional levels are allowed to develop and offer a limited number of elective courses. The national curriculum covers competencies from 11 educational areas: arts and culture; communications; English as a foreign language; mathematics; personal development, citizenship, and civics; physical education; religion (also non-compulsory); science and technology; social sciences; the Spanish language; and vocational education. Depending on the type of school, hours of instruction range from 30 to 45 hours a week.

Although curricula for both academic and vocational streams cover all 11 educational areas, the amount of time devoted to each area varies. Compared with the general academic stream, the vocational stream requires that nearly three times as many weekly hours be devoted to vocational education, while requiring fewer hours for arts and culture, physical education, and electives.

According to INEI data, nearly 2.6 million students were enrolled in secondary education in 2019, around 5 percent less than their peak in 2007. Although Peru’s shrinking youth population has caused overall secondary enrollment to decline, in recent years more and more eligible Peruvians have begun enrolling in secondary education. Since 1970, Peru’s secondary GER has grown steadily, reaching 100 percent for the first time in 2016.

Learning outcomes have not improved quite as steadily. Peru’s performance on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has long been disappointing. The country was ranked last in all three tested fields (mathematics, reading, and science) in both 2000 and 2012. Although Peru’s scores in all subjects improved in the 2018 PISA, the most recent, they still ranked in the bottom quintile of an expanded set of countries.

The 2018 PISA also revealed stark differences in performance between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged Peruvians. Just 18, 14, and 19 percent of students from the lowest income quintile achieved the minimum level of proficiency in reading, mathematics, and science, respectively, at the end of lower secondary compared with 75, 68, and 74 percent of students from the highest income quintile. PISA data also reveal that socioeconomic differences play a bigger role in determining learning outcomes in Peru than in nearly every other participating country. According to an OECD analysis of the scores, economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS) explained 21.5 percent of the variance in reading scores in Peru, the highest level of all participating countries. The impact of ESCS on Peru’s mathematics and science scores were similar.

As is the case at all levels of Peru’s education system, quality and outcomes at the secondary level vary considerably between different areas of the country. While the secondary graduation rate for adults older than 15 stood at 44 percent nationwide in 2019, it ranged widely between different regions: from a low of 35 percent in Cajamarca to a high of 52 percent in Madre de Dios. The learning outcomes of students from rural areas and Indigenous communities also tend to trail those of students from urban areas, at times by significant margins.

Peruvians can obtain technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in a variety of educational settings, both formal and informal. As discussed above, in the final three years of secondary education, students can enroll in a vocational stream. They can also enroll in post-secondary TVET programs at either universities or non-university higher education institutions, both of which are discussed below.

But Peruvians can also obtain vocational training, or educación técnico-productiva, at vocational training centers (centros de educación técnico-productiva, CETPRO), which have traditionally operated outside the formal education system. Educación técnico-productiva prepares individuals with the skills and competencies needed to perform particular vocations. Ministry regulations note that vocational training should prioritize underprivileged populations, especially those in rural communities.

Sizable numbers of students enroll in educación técnico-productiva programs: In 2019, slightly more than a quarter-million students were registered in either public or private CETPROs. Private institutions make up more than half (roughly 58 percent) of the nearly 2,000 CETPROs nationwide, although they train relatively few students. According to Peru’s 2020 education census, many private CETPROs enrolled fewer than 10 students. Although fewer in number, public CETPROs enrolled the majority of students (58 percent, or nearly 146,000 students) in 2020.

For years, CETPROs have offered programs in a variety of fields at two different levels: the basic-level (ciclo básico), which has no formal academic admission requirements; and mid-level (ciclo medio) programs, which require completion of basic-level training or elementary education for admission. Until recently, basic-level students successfully completing 1,000 study hours obtained a título de auxiliar técnico (title of technical assistant); mid-level students completing 2,000 study hours obtained a título de técnico (title of technician).

But in March 2019, MINEDU introduced a reform to better integrate educación técnico-productiva programs with the formal secondary and post-secondary education system. Although the reform retains both the título de auxiliar técnico and the título de técnico, it increases the academic workload of both programs and adjusts their structure.

As before, the post-reform auxiliar técnico programs will have no minimum academic entry requirements; admission will be open to all Peruvians of at least 14 years of age. However, auxiliar técnico programs will now use Peruvian academic credits, requiring the completion of 40 credits (or around one year of full-time study). The reform also opens a pathway for students obtaining a título de auxiliar técnico to transfer into the second cycle (the final three years) of secondary education.

The impact of the reform on técnico programs is similar. These programs will still be open to those who have completed elementary education. However, once enrolled, these students will now be required to complete 80 academic credits, or around two years of study, to graduate. Graduates will be awarded a título de técnico and will be eligible for admission to non-university post-secondary institutions. Although auxiliar técnico and técnico programs remain non-sequential, provisions in the reform do allow holders of a título de auxiliar técnico to transfer relevant credits earned in that program to título de técnico programs.

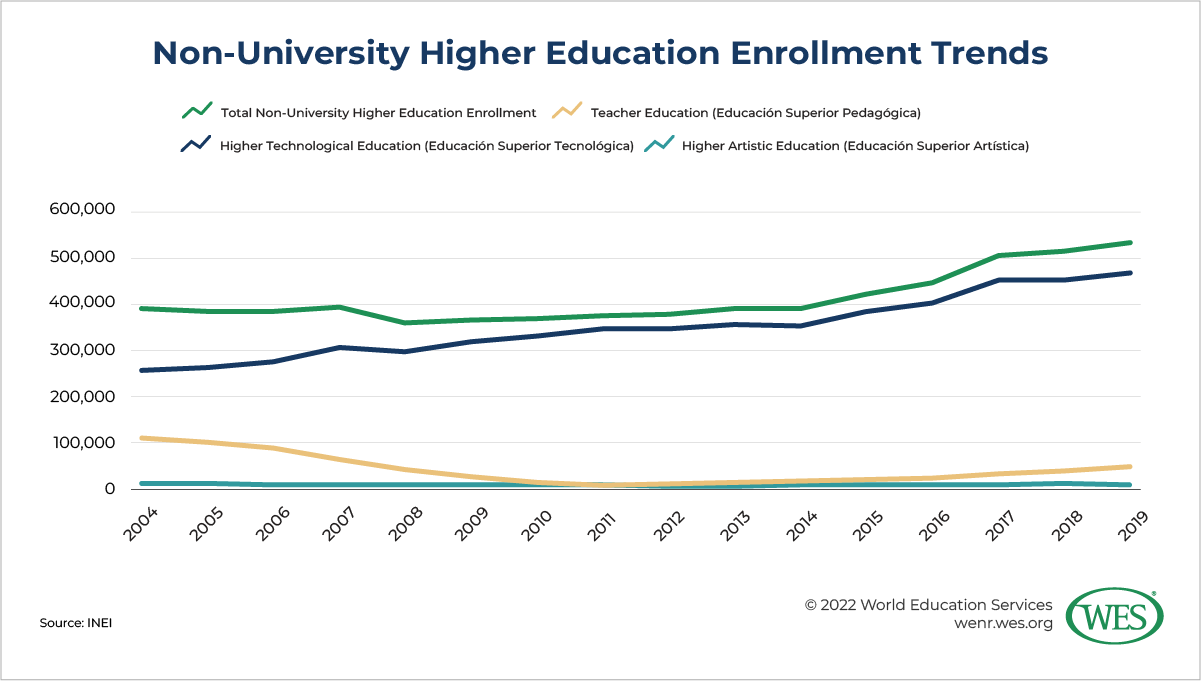

As mentioned above, non-university higher, or post-secondary, education (educación superior no universitaria) is divided into three types: higher technological education (educación superior tecnológica), higher artistic education (educación superior artística), and higher pedagogical, or teacher, education (educación superior pedagógica). Institutions at this level enroll a sizable number of students, nearly 510,000 in 2018, or around 55 percent of the number enrolled in universities that year.

As at other levels of Peru’s education system, the quality of education varies widely at different non-university higher education institutions across the country. To address these discrepancies, recent reforms have adjusted institutional licensing requirements, raising the minimum standards that institutions must meet with respect to their academic and institutional management, infrastructure, faculty, financial resources, research, and complementary services, like student support and employment support assistance. The introduction of this reform in 2020 was accompanied by a temporary suspension of license applications for these institutions. Observers predict that many non-university higher education institutions will be unable to meet the elevated licensing standards and be forced to close.

By far the most popular type of non-university higher education is educación superior tecnológica, or higher technological education. In 2019, around 89 percent, or 467,826 students, of all students enrolled in non-university higher education programs were in enrolled in higher technological education programs. Educacion superior tecnologica programs provide education and training in science, technology, and liberal arts subjects that are in demand in the labor market.

Programs at this level are typically offered by institutos or escuelas de educación superior tecnológica (higher institutes or schools of technology, IEST or EEST). In 2020, around 870 of both types of institutions were operating. About 42 percent of these were public or government-financed; the rest, private. On average, the student body at public institutions is significantly smaller than at private institutions. In 2019, public EESTs and IESTs enrolled around 363 students each, while private institutions enrolled about 666 students.

Ongoing reforms, first introduced in 2016, grant EESTs more academic and administrative autonomy than IESTs, and encourage IESTs to convert to EESTs. To improve educational quality, these reforms also require all non-higher education vocational and training programs to be modified in collaboration with academic secondary and post-secondary institutions. These reforms also prioritize mobility between the university and non-university subsystems, expanding pathway options between the two sectors.

Since the introduction of these reforms, EESTs and IESTs have offered programs of study leading to four principal titles: the título técnico (title of technician), the título de profesional técnico (title of technical professional), the título de professional (title of professional), and the título de segunda especialidad (title of second specialty). These programs utilize a credit system similar to that already in use at the university level. These titles are not awarded exclusively by educación superior tecnológica institutions. As discussed below, they can also be awarded both by other non-university higher education institutions and university-level institutions.

Offered by both IESTs and EESTs, título técnico de educación superior programs require a minimum of 80 Peruvian credits, or two years of post-secondary study. Admission is restricted to students possessing a secondary school certificate or its equivalent. These programs are typically offered in applied science fields.

The current education law includes a provision allowing post-secondary institutions to validate the studies of graduates of certain CETPRO programs in order that holders of the título de técnico can obtain a título técnico from a higher education institution.

Offered in applied science and technology areas by both IESTs and EESTs, the grado de bachiller técnico (technical bachelor’s degree) requires the completion of three years of study and a minimum of 120 Peruvian credits. Admission is restricted to students who have completed secondary school or its equivalent. Students are also required to study or otherwise demonstrate their previous knowledge of a foreign or Indigenous language.

Since the 2016 reforms, students awarded a grado de bachiller técnico have also been able to earn a título de profesional técnico (title of professional technician) if they complete a professional internship or a professional proficiency examination.

Recent reforms have also authorized EESTs to offer programs in professional fields leading to the award of a grado de bachiller (bachelor’s degree), a degree previously awarded exclusively by universities. As with other undergraduate university degrees, these programs require a minimum of five years of study and 200 Peruvian credits and are open only to students completing secondary education. Students are also required to complete a research project and confirm their knowledge of a foreign or Indigenous language prior to graduation.

The reforms also opened pathways to graduate study for students in these programs. Students obtaining a grado de bachiller from an EEST are now eligible for admission to graduate programs at university-level institutions.

Those wishing to obtain a título profesional (title of professional)—the most common of which is a title of teacher, discussed below—must complete a thesis or degree project after being awarded a grado de bachiller. Universities also offer grado de bachiller and a título profesional programs.

Since the introduction of the current education law, EESTs have also been able to offer título de segunda especialidad (title of second specialty) programs, a post-graduate specialization degree previously awarded exclusively by universities. These programs require an undergraduate degree for admission. Graduation requirements include the completion of a minimum of 40 Peruvian credits, or around one year of study, and the drafting and defense of a thesis or the completion of a degree project.

Título de segunda especialidad degrees, as well as the grado de bachiller técnico and the grado de bachiller, awarded since 2016 are registered in a national database and can be verified online.

Post-secondary non-university study is also conducted at institutos y escuelas superiores de educación de formación artística (higher institutes and schools of art, IESFA), although relatively few students enroll in these programs. In 2020, the country’s 32 public and six private IESFAs only enrolled about 6,000 students in total. These institutions typically offer título de profesional programs in a variety of art-related fields.

In recent years, some IESFAs have applied for and been granted university-level status. Besides being able to offer licenciado degrees, those institutions elevated to the level of university also enjoy a larger degree of administrative, academic, and financial autonomy, allowing them to better compensate their faculty and staff. Rising pay at the newly created art universities has generated debate about the need to improve conditions at non-university institutions and close the wide gaps that exist in faculty pay between non-university and university-level higher education institutions.

Teachers working at Peru’s public elementary and secondary schools have traditionally earned precarious wages. To get by, many take on second jobs. Peru’s public school teachers union estimates that nearly 50 percent of teachers engage in additional income-generating work. Although in 2020, the government raised the starting salary of basic education teachers to 2,400 soles a month (around US$600 at the 2020 exchange rate)—a level 54 percent higher than in 2015—teachers still earn less than other similarly educated professionals in Peru. That said, their salaries are comparable to those of their counterparts in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

In the past, teachers were predominately trained at institutos de educación superior pedagógicos (higher institutes of teaching, IESP), where they studied for five years to earn the título de profesor (title of teacher), which was required to begin teaching at a basic education school.

More recently, reforms have aimed at transforming these IESPs into escuelas de educación superior pedagógicos (higher schools of teaching, EESP), which, in addition to the título de profesor, offer the grado de bachiller, a degree previously restricted to universities. IESPs had until June 30, 2021, to request licensing to convert to EESPs. The new law also authorizes teacher training institutions to offer título de segunda especialidad programs.

Either a título de profesor or a título de licenciado in education is required to teach at a basic education school in Peru. To earn either of these titles, students must currently first obtain a grado de bachiller (bachelor’s degree), which requires the completion of five years of post-secondary study—or at least 200 Peruvian credits—the completion of a thesis or degree project, and a demonstrated knowledge of at least one foreign or Indigenous language. Students obtaining a grado de bachiller are eligible to enroll in graduate programs offered at university-level institutions. After earning the bachiller, students must complete an additional thesis or degree project to earn a título de profesor or a título profesional.

As of 2021, there were more than 100 public EESPs and IESPs operating in Peru, each enrolling on average 336 students. Private teacher training schools and institutions, of which there are currently 85, tend to enroll fewer students, with average enrollment reaching 204.

University education, educación superior universitaria, is the other half of Peru’s higher education system. Although recent reforms have augmented the privileges of the non-university higher education institutions, universities continue to enjoy a greater degree of academic, administrative, and financial autonomy. They are also authorized to award all undergraduate and postgraduate degrees and titles.

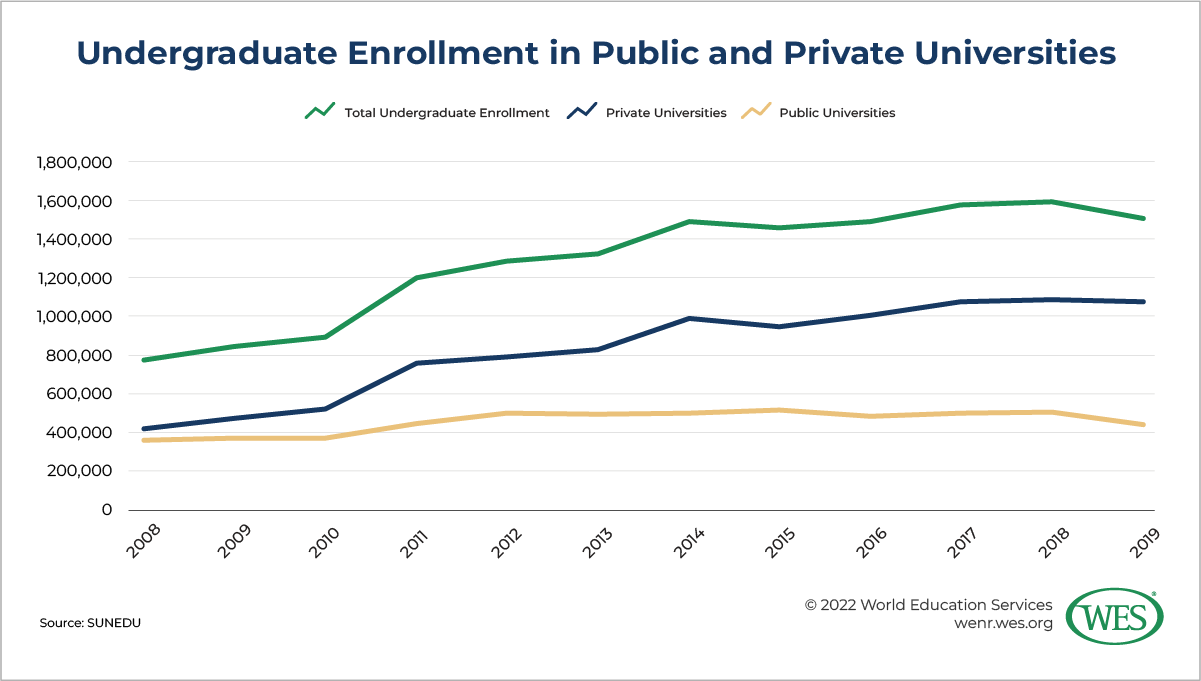

University-level institutions also enroll many more students than non-university higher education. Their popularity has soared over the past two decades. Since the start of the twenty-first century, university enrollment in Peru has grown faster than anywhere else in Latin America. Between 2008 and 2018 alone, undergraduate enrollments more than doubled, growing from around 772,000 to 1.6 million.

Much of this growing demand has been absorbed by private universities. Between 2000 and 2019, while public institutions grew modestly, from 32 to 48, private institutions more than doubled, growing from 42 to 91. Aided in part by a 1996 law that granted tax breaks to for-profit organizations investing in education, most of these newly established private institutions have been profit-making enterprises. Over the same period, for-profit private institutions grew from 13 to 50, while non-profit private institutions grew from 29 to 41.

As a result, the share of total university enrollment in private institutions increased sharply. In 2008, private institutions enrolled a bit over half (54 percent or about 415,000 students) of all university students. By 2018, they enrolled more than two-thirds (68 percent or nearly 1.1 million).

In large measure, this massive expansion was not accompanied by improvements to the country’s quality assurance mechanisms. Until recently, universities were subject to minimal government oversight, leading observers to lament the low quality of many of Peru’s universities, especially the country’s rapidly multiplying for-profit institutions.

In 2014, these concerns finally prompted Peru’s government to take action. That year, after more than a decade of debate, parliament adopted a new university law aimed at improving the quality of education, scientific research, and innovation at the country’s universities, both public and private. Its provisions raised the minimum standards for teaching staff, requiring that at least a quarter of an institution’s faculty teach on a full-time basis and that all teaching staff hold at least a master’s degree, or, for teaching staff in doctoral programs, a doctorate. Improvements to the content of university programs were also made, as provisions introduced foreign language and general education requirements to many degree programs. The law also required all universities to obtain licensing to begin or continue operating, a process requiring them to meet heightened quality standards concerning infrastructure, technological resources, faculty, research activities, and financial viability.

The licensing requirements have had a particularly transformative impact on the country’s higher education landscape. Since the law’s adoption, more than a third of once-operating universities in Peru have been forced to close. To date, educational authorities have denied licenses to 51 5 poorly performing university-level institutions, all but three of which were private. These institutions are prohibited from enrolling new students, and must transfer existing students to licensed institutions and cease operations within two years. 6 Some of their leaders and administrators have been subsequently accused of negligence or economic corruption and embezzlement.

The impact of these denials has been enormous. Three of the five fastest growing universities over the last decade—all private—received denials. Among them was the Universidad Alas Peruanas which, in less than 25 years, had grown to become the country’s largest provider of higher education. Together, the 51 institutions receiving denials enrolled around a quarter (23 percent in 2016) of all university students. Combined with the impact of demographic changes and the COVID-19 pandemic, the denials are likely to drive sharp enrollment declines in the coming years.

These quality issues also spurred the government to devote additional funds to the higher education sector. Between 2011 and 2019, average per-student university education spending across all regions rose from 6,300 to 9,116 soles, or roughly US$2,750 at the average 2018 exchange rate. Still, funding levels trail significantly behind that of Peru’s neighbors. Despite the increase, per capita spending remains roughly a third of neighboring Chile’s, and well below the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of $17,100.

The increase also seems to have done little to improve the quality of Peruvian higher education. Peruvian universities remain largely absent from world or regional quality rankings. In the latest 2021 Times Higher Education ranking of Latin American Universities, only one Peruvian university ranked among the region’s top 50 (the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, ranked 36 th ), compared with 29 Brazilian, 7 Chilean, 4 Colombian, 3 Mexican, and 3 Argentine universities. Results from the other major international university rankings were similar.

The overall increase in funding also hides glaring regional disparities. In 2018, per capita investments at the university level varied considerably between different regions of Peru, ranging from 27,368 soles in the region of Moquegua to just 4,832 soles in the region of Junín. In fact, the rapid expansion of university-level institutions largely bypassed rural and impoverished areas of Peru. In 2019, out of 774 educational entities (including satellite campuses) only 18, or about 2 percent, were located in rural areas; only 2 of those were main campuses.

It also hides significant socioeconomic disparities. While a little under half (48 percent) of all university-age Peruvians from the highest income quintile entered a university in 2018, just 9 percent of those from the lowest income quintile did so.

To address these disparities, Peru has introduced university scholarship programs for low income and outstanding students. These include the Beca 18, which funds the studies of 5,000 low-income secondary school graduates, and the Beca Permanencia, which finances 8,000 outstanding students enrolled in public universities. However, given the yawning disparities that currently divide the country, it is unlikely that public measures taken to date will do much to equalize access.

The 2014 university law also revised quality assurance and accreditation mechanisms in the country. Among its most important outcomes was the creation of the Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Universitaria (SUNEDU) which it charged with supervising the quality of higher education throughout the country and licensing higher education institutions.

As a result of the new law, universities must obtain a license from SUNEDU to begin or continue operating. To obtain licensing, universities must meet basic quality standards concerning their:

Universities obtaining a license must have it renewed every six, eight, or ten years, the length determined by the extent to which they meet these basic quality conditions. To date, only a handful of institutions have obtained the longest ten-year license. SUNEDU also evaluates post-secondary non-university institutions, to which it issues five-year renewable licenses.

The 2014 university law also reorganized the already existing Sistema Nacional de Evaluación, Acreditación y Certificación de la Calidad Educativa (SINEACE), which works alongside SUNEDU to ensure the quality of education provided by the country’s higher education institutions.

SINEACE’s responsibilities include accrediting institutional and program quality, a voluntary process available to licensed universities, non-university higher education institutions, and CETPROs. University programs are typically accredited for six-year cycles, although if a program does not meet all accreditation standards, it may be granted conditional two-year accreditation and given the opportunity to rectify shortcomings and obtain the full six-year accreditation. Health-related programs offered by post-secondary non-university institutions are usually accredited for two- or three-year cycles.

SINEACE’s accreditation process relies on institutional self-assessments and site visits conducted by external evaluation entities. As the process is voluntary, not all institutions choose to have their programs accredited. As of October 2021, the public registry maintained by SINEACE on its website only listed 259 accredited programs.

Admission criteria at Peruvian higher education institutions vary considerably depending on the program and institution. Although all admitted students must have at least completed secondary education, academic institutions can develop more detailed admission requirements on an institution-wide or a program-specific basis.

Most universities set minimum secondary school grade point averages (GPAs) and administer entrance examinations. Universities often administer two sets of entrance examinations: one general and one program-specific. The current university law also envisions, and some institutions have already adopted, a number of different university admissions modalities, including direct admissions pathways from pre-university centers to associated universities; and reserved public university seats for high performing secondary school students and athletes. The government also already reserves a small proportion of university seats for individuals with disabilities and victims of the violence that plagued Peru from 1980 to 2000.

Admission to some programs and universities can be fierce. As a result, some students spend up to two years at private, pre-university centers preparing for university admissions examinations. Competition tends to be especially intense at the country’s public universities. While Peruvian universities accepted about half of all applicants in 2017, public universities admitted less than one in five.

Private institutions, on the other hand, are much less selective. In 2017, rejection rates at Peruvian private universities were nearly four times lower than at their counterparts in the public sector. For-profit private universities are the least selective: In 2017, they admitted more than 75 percent of all applicants. The newly introduced university licensing process, and the resulting closure of dozens of low-quality private universities, is likely to reduce that percentage in the coming years.

In 1969, the now defunct National Council for Peruvian Universities (Consejo Nacional de Universidad Peruana, CONUP) introduced a national standardized credit system. Under this system, one Peruvian credit was defined as one hour per week of classroom instruction or two hours per week of practical training. This system also set the standard length of an undergraduate degree program at 200 Peruvian credits, with a 10 percent margin upwards or downwards (that is, 180 to 220 credits).

This system remains more or less intact to this day. The current university law defines one credit as equivalent to at least 16 hours of classroom instruction or 32 hours of practicum training. Most undergraduate programs, except those in professional and regulated specializations, still require 200 credits or at least 10 semesters of study.

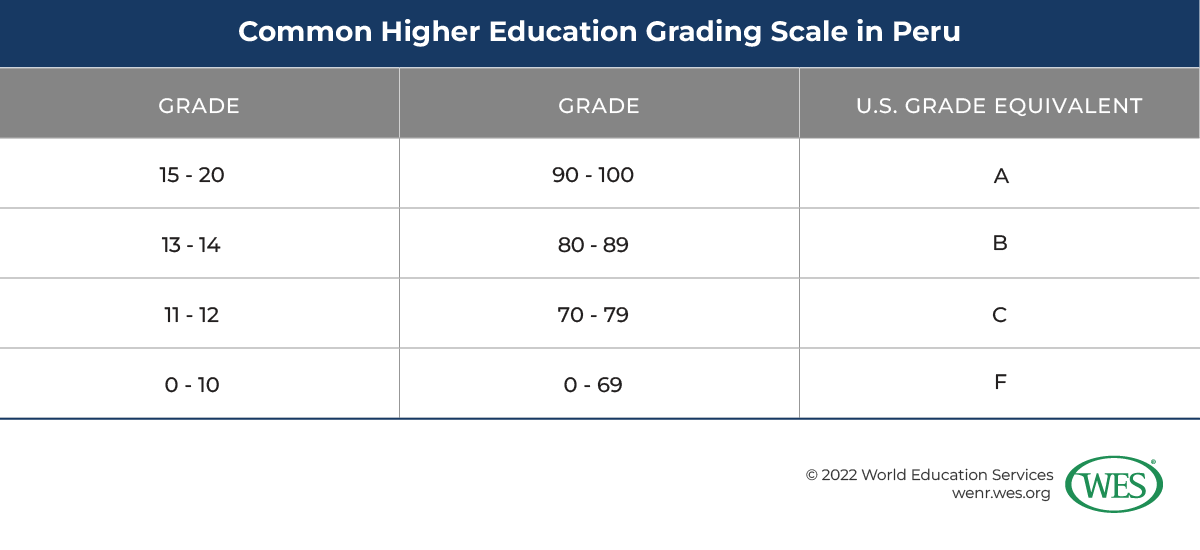

Grading scales have not been standardized to quite the same degree. Still, although grading scales can vary by institution and program, most institutions have adopted a 0 to 20 grading scale. Under this system, the minimum passing grade is typically 11 for undergraduate programs, although it may be 12 or 13 for graduate programs.

The 2014 university law also impacted university degree programs. It introduced important changes at the undergraduate level, including a foreign language (preferably English) proficiency requirement, and a general education requirement (set at a minimum of 35 Peruvian credits).

SUNEDU maintains a public database, available online, through which all degrees awarded since 2016 by university-level institutions can be verified.

At the undergraduate level, grado de bachiller, or bachelor’s degree, programs require a minimum of five years of study and the completion of 200 Peruvian credits, although programs for some regulated professions, such as law, psychology, and medicine, generally require more than 10 semesters of study. As noted above, at least 35 credits must be earned in general education courses, with the remainder obtained in specialization courses or electives. Since the 2014 university law was adopted, students have also been required to complete a final research project and demonstrate their knowledge of a foreign or Indigenous language to be awarded the grado de bachiller.

Students obtaining a grado de bachiller can also earn a título de licenciado (title of licentiate) or a título profesional de licenciado (professional title of licentiate). These licenciado degrees are protected titles in Peru and can only be awarded by university-level institutions. To qualify, students must typically draft and defend a thesis or complete a project beyond those required for the grado de bachiller.

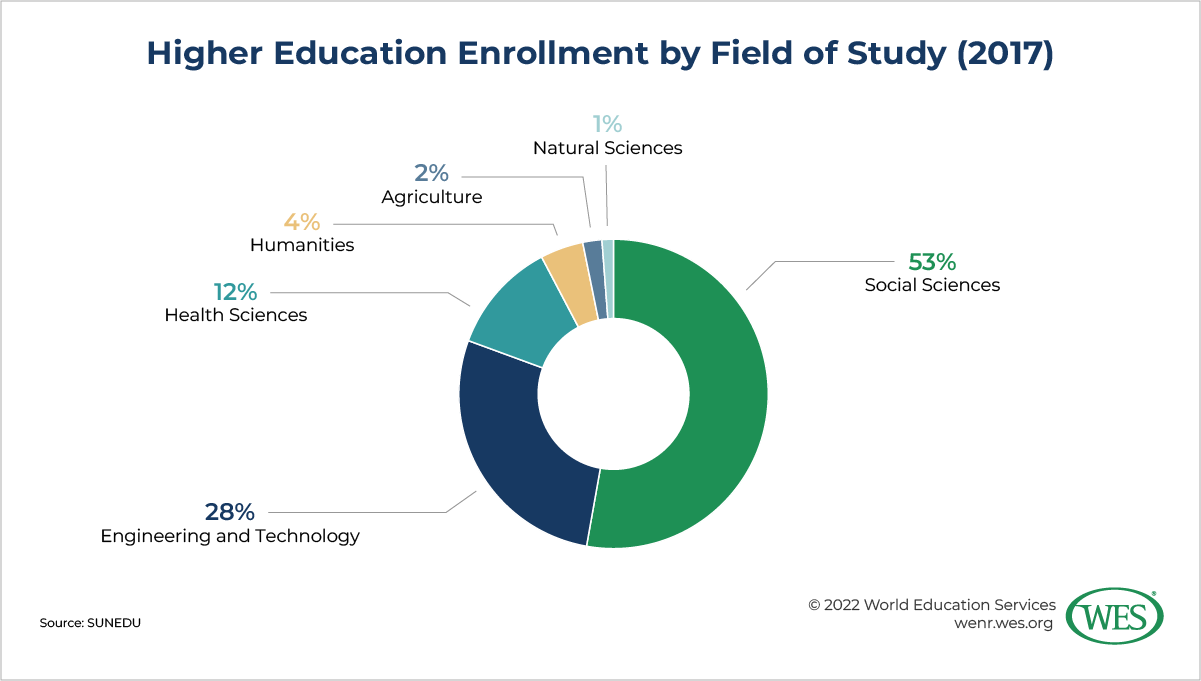

Undergraduate programs are offered free of charge at public institutions. According to SUNEDU, licensed Peruvian university-level institutions offered around 3,400 degree programs leading to the título de licenciado or título profesional in 2021. Social science programs are the most popular, enrolling more than half (53 percent) of all students, followed by programs in engineering and technology (28 percent), health and medical sciences (12 percent), the humanities (4 percent), agriculture (2 percent), and the natural sciences (1 percent). On a slightly more granular level, SUNEDU statistics reveal that the business sciences (such as business administration, tourism, marketing, and human resources), law, and education are among the most popular fields of study.

Título de segunda especialidad (title of second specialty) programs offered by university-level institutions require a minimum of 40 Peruvian credits or two semesters of full-time study. To be admitted to these programs, students must hold an undergraduate degree. To graduate, students typically need to write a thesis or present a final project.

Segunda especialidad programs in medical fields that require a period of clinical residency are regulated by specific legislation and maintain a different set of admission, academic, and practical requirements. According to SUNEDU, in 2021 licensed Peruvian university-level institutions offered more than 1,900 programs leading to the título de segunda especialidad.

To be admitted to a grado de maestro, or master’s degree, program, students must have obtained an undergraduate grado de bachiller degree. Grado de maestro programs require the completion of a minimum of 48 Peruvian credits or two semesters of study. Like other levels, the grado de maestro typically requires students to demonstrate proficiency in a foreign or Indigenous language and to complete a thesis or degree project to graduate.

According to SUNEDU, in 2021 there were nearly 2,200 degree programs leading to the grado de maestro offered by licensed Peruvian university-level institutions.

Grado de doctor, or doctoral, programs require a master’s degree for admission. They require students to complete a minimum of 6 semesters or 64 Peruvian credits of advanced graduate study, demonstrate proficiency in 2 foreign languages, one of which may be substituted by an Indigenous Peruvian language, and draft and successfully defend an original thesis. According to SUNEDU, Peruvian universities offered slightly more than 400 degree programs leading to the grado de doctor in 2021.

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below:

1. In 2018, the Lima Chamber of Commerce (CCL) defined the middle class as anyone with an income ranging “between US$10 and US$50 a day, measured on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis, which is equivalent to a monthly income of between S/1,942 (US$584) and S/9,709 (US$2,920),” or between US$7,008 and US$35,040 per year.

2. Eligible universities must be ranked among the top 400 globally in any of the three major international university rankings: the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), the QS World University Rankings, and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.

3. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students. This lack of consistency is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, definitions of international student, and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). The policy of WENR is not to favor any given source over another, but to be transparent about what we are reporting and to footnote numbers that may raise questions about discrepancies.

4. Globally, among all U.S. study abroad destinations, Peru was the 19 th most popular study abroad destination in the 2018/19 academic year.

5. Since the reforms were passed, 50 non-university higher education institutions received licensing from SUNEDU and were granted university-level status.

6. An updated list of institutions unable to obtain licensing is published on the SUNEDU website.